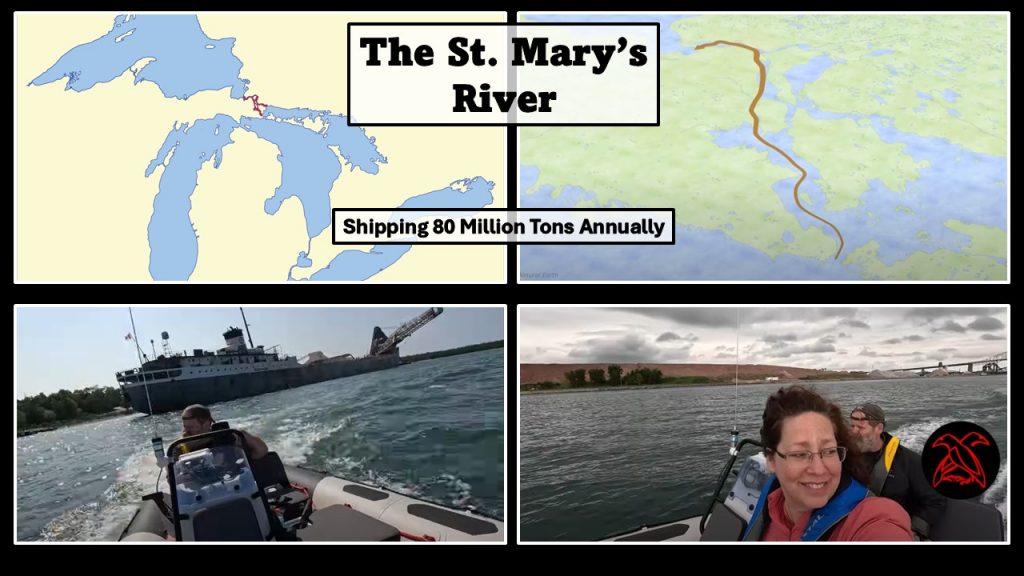

Annually, the St. Mary’s River guides over 80 million tons of ore, coal and limestone along the 74 mile route connecting Lake Huron to Lake Superior. A freighter completes this journey in nine hours, while it took us two days in our 16-foot zodiac.

Map Credit: Chuck Hayden

We traversed this ancient, indigenous trade route, sought out the only British Fort on American soil, toured a ship in the woods, examined Lime Island’s industrial scars, located a governor’s quiet refuge and went through the Soo Locks. Join us on our historical adventure!

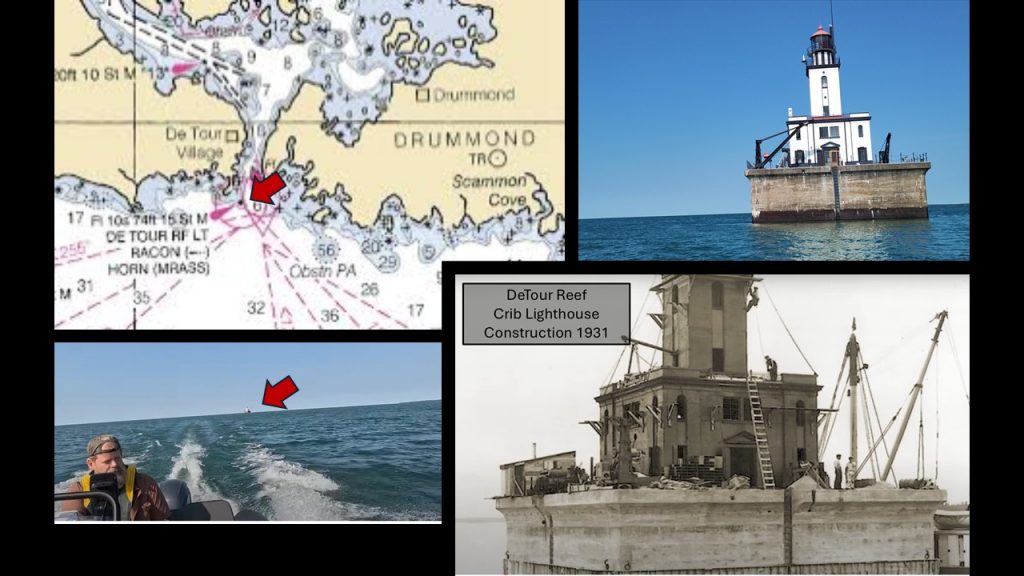

DeTour Crib Lighthouse

We started our journey in Lake Huron at the DeTour Lighthouse by Drummond Island. This crib lighthouse stands in the middle of the passage, marking a shallow shoal. Originally built on shore in 1847, the light had been moved out to the water in 1931 as a crib lighthouse. This relocation made it a better beacon for mariners.

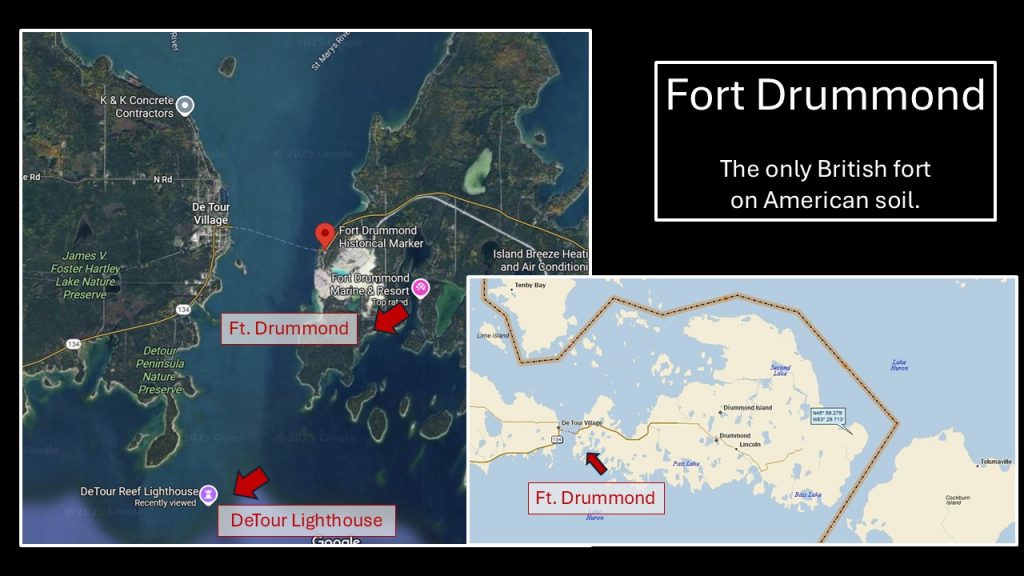

Next we swooped around the southern peninsula of Drummond Island and into the cove where Fort Drummond had once stood.

Fort Drummond

Fort Drummond has been the only British fort on American soil. When it comes to property; it’s all about location, right? Well, this cozy cove on Drummond Island’s southern side met the British soldier’s needs. Believing this had been British land, construction had started in 1814.

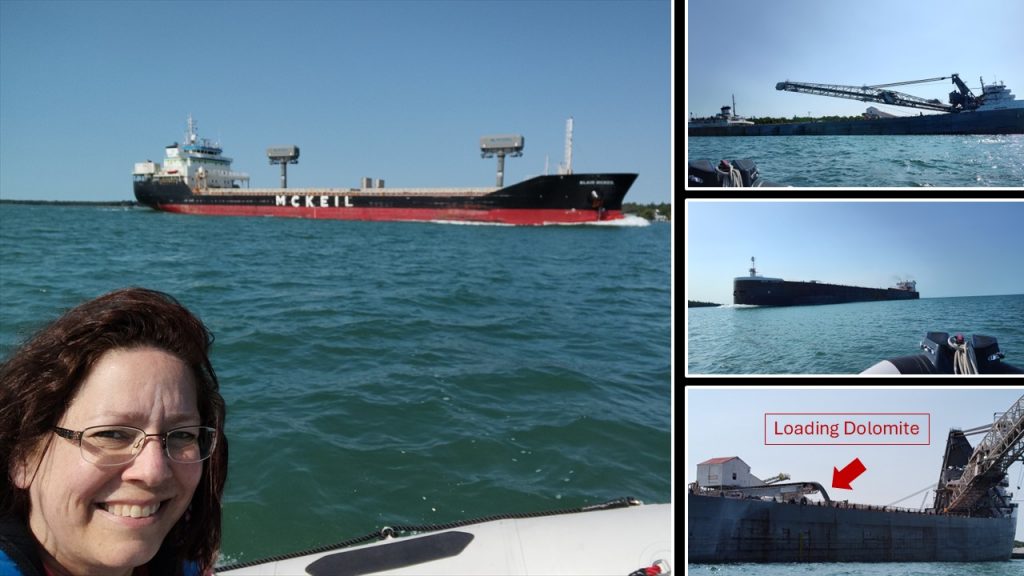

This magnesium-rich Engadine dolomite is used as an additive in agriculture, as flux in steel making and as an aggregate in construction.

Map Credits: Drummond Island Tourism and “A Landing Day” blog

When the British military lost Fort Mackinac in 1815, they relocated to the newly built, Fort Drummond, which they believed to have been on British soil.

After years of a bitter land dispute, a team of surveyors in 1822 determined that Drummond Island was, in fact, a United States property. But with this ideal location, the Brits stayed for another six years before they relocated once again.

Long after it was abandoned, a forest fire destroyed the wooden structures. Today, only the whispers from a cemetery and a stone chimney remain.

Ships Everywhere!

As traversed around the peninsula, back to the St. Mary’s River, two ships came into view. Then we noticed another along a dock being loaded with dolomite.

Watching ships is a hobby for many people. Most download an app, “Vessel Finder,” to follow ships as they move through the Great Lakes and the St. Lawrence Seaway.

Being alongside these mammoth movers, I felt like a tiny creature. One of my favorite ships is the Edwin H. Gott. This 1,000 footer was built in 1979.

Edwin H. Gott

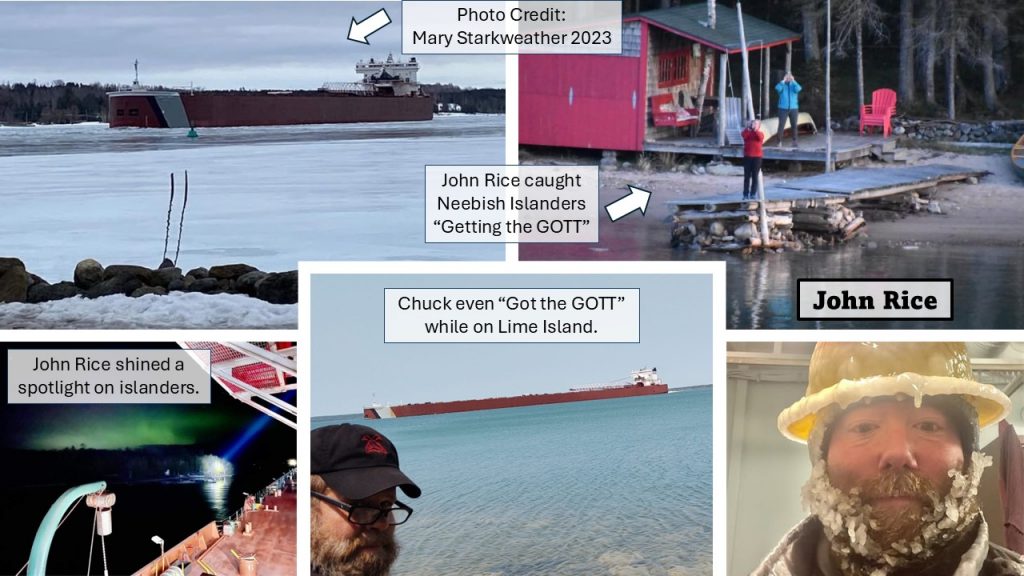

John Rice, a wheelman aboard the Gott, began a Facebook page, “Got the GOTT” several years ago. People would post photos of the vessel along its Great Lakes route. While John Rice would post pictures of people on shore, who were taking pictures of the Gott. Neebish Islanders appear frequently.

Photo Credit: Got the GOTT Facebook page and (center) Chuck Hayden

I was hoping to catch a glimpse of the GOTT on this trip, instead we spied another ship’s bow pointing out from the a wooded scape. This had been a puzzling sight!

The Ship in the Woods – John W. Boardman

Designed to haul cement in 1923, the John W. Boardman has been given a new life in 2010. Marc and Jill purchased the bow, wheelhouse and forward cabins from the scrap yard. They hired a company to roll the metal mammoth onto their shoreline property from a barge. A true engineering feat!

Over the past fifteen years we’ve admired the progress of restoration for this iron giant. The rusty vessel had been so dingy years ago when we first witnessed, “The Ship in the Woods.”

The dedicated couple, Marc and Jill, have been breathing life back into this ship! It has been lovingly transformed.

As we drew closer to the ‘ship in the woods’ we heard a voice from the bow, “Is that the Restless Viking people?” It was Marc, the owner, calling to us! Chuck responded, “Yeah! If you don’t mind coming down, we’d love to talk with you.” Marc waved his hand, “You can pull in there. It’s ours. You can tie off.” His head disappeared as he made his way down to their dock to greet us. “Do you have time for a tour?” Marc asked as we secured Sea Raven.

Butterflies bee-bopped in my belly as I tried to tie the lines and grab the cameras. After seeing this piece of art from afar, we were going to see inside! What a fortunate treat!

Standing at the bow with Marc was an unexpected treat!

Marc had a bounce in his step as he led us up the hill. He described the massive chore of moving the vessel onto the hill next to their family cabin. Then, Marc unlocked the door and led us over the threshold.

It was as if we’d stepped into another era. The wood-paneled walls gleamed. Marc and Jill have worked to assemble time-period pieces inside the Captain’s office, the cockpit and the cabins.

Next, Marc led us down a steep stairway, going below deck. The sun baked us inside the metal walls. The massive iron chains, metal rivets and water spickets spoke to us from decades ago. This labor intensive, dangerous work helped move cargo across the Great Lakes’ region.

Marc’s energy radiated throughout the ship. His sage knowledge brought me an appreciation for the wheelsmen aboard these vessels. We could have spent days with Marc and Jill, absorbing information, but we had to press on.

After we traded business cards and added a donation in their “paint bucket collection,” we shook hands, bidding them well. I admire this dynamic duo, Marc and Jill. Their dedication and commitment has settled in my soul. I was quiet as we boarded Sea Raven, pondering all that we’d witnessed. I will always cherish our time with Marc and Jill.

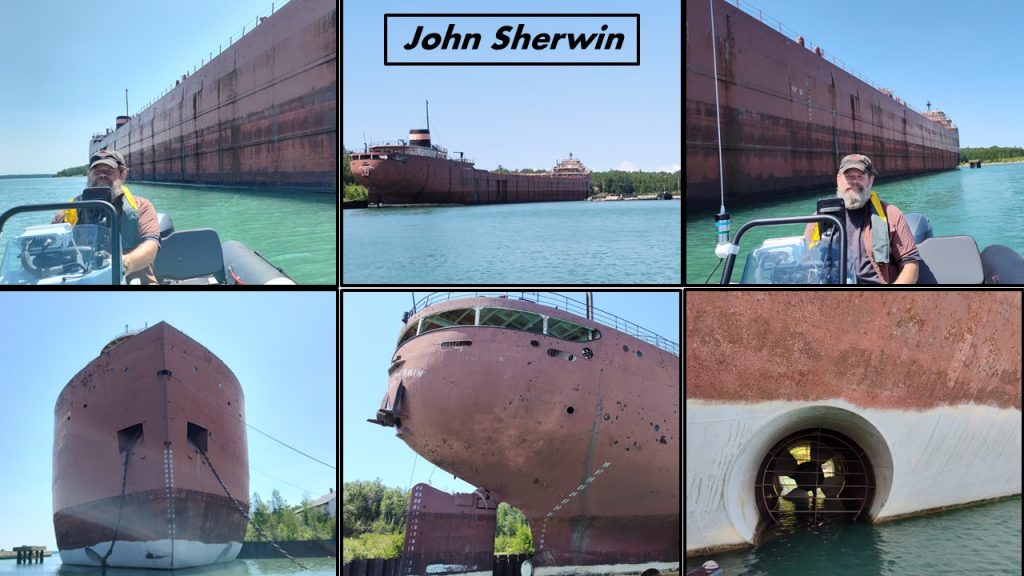

“The John Sherwin has been docked over there for decades.” Chuck gestured to the north. I released the line and we were off once again ready to investigate.

John Sherwin

Waiting patiently along the shoreline is an iron and coal hauling giant, the John Sherwin. Birds, aboard the boat, announced our arrival. Coming up alongside this vessel was fascinating. The ship’s body stretched over 700 feet long.

Built in 1957 without a “self unloader” system, this ship constantly cost more to unload. Constructed with this “set-back,” the John Sherwin has continued to be seen as a burden, waiting for its time to shine.

After a couple of decades in operation, the John Sherwin was slated to be converted to a ‘self unloading’ system. But in the early 1980’s the Recession had taken a tight hold of the shipping industry. The extra funds weren’t available.

Twenty years later, plans began brewing again, to make the unloading modification as well as converting the engines. But with the economy’s downturn in 2008, plans stalled once again. So, the vessel is still waiting for a re-stylization. Meanwhile, the seagulls and cormorants have taken up residence. I am curious to see what will happen to the John Sherwin.

Next, we cut through waves, heading north to Lime Island State Park. Since 1981, Lime Island has drawn more and more visitors each year. The trick is, you need a boat to get there, but it’s worth it!

Lime Island State Recreation Park

Lime Island has been one of our family traditions since our kids were young. Over 600 acres of frolic and fun, plus a view of freighters day and night. Many memories have been made for us here!

Lime Island’s history, however, has stretched out over centuries. The Anishinaabe had met on this island. It had been a stop over for trading and challenging other tribes in a game similar to lacrosse.

In the 1790’s sixteen lime kilns were discovered. These had been used to process limestone for the construction Fort St. Joseph, located across the river in Canada.

Would you believe, in 1890 the Davenport Hotel, with thirty rooms, was constructed where the cabins sit today? There had been hope that this hotel would attract tourists, like the Grand Hotel on Mackinac Island, which had opened three years earlier in 1887.

Apparently, movie star, Mae West, had once stayed at the Davenport Hotel. But, without direct rail lines or regular steamship transportation, Lime Island’s tourism had never taken off. Instead, the island became an essential refueling stop for passing freighters.

Around the 1900’s Lime Island became a regular stop for steamships’ coal refueling. A bunkhouse for workers was built near the shore. Some of these men had their families relocate to Lime Island. A row of homes lined the center of the island. To accommodate this new community, a one-room school was built in 1913 as well as a post office!

When ships no longer needed refueling, the community disbanded and the school closed in 1961.

When coal fell out of favor, diesel fuel took its place. Enormous tanks were placed along the shoreline. Refueling continued at the Lime Island dock, but with a different product. Later as ships became more efficient, refueling was no longer needed. The community disbanded and the school closed in 1961.

Since the 1980’s, work to re-imagine this island paradise into a State Park took hold. Cabins were built using solar shingles. Camping platforms were constructed. The school and superintendent’s home were made into museums. With Lime Island’s location, being right along the shipping channel, it’s a great get-away!

With one last look up the hill, Chuck and I continued north along the east side of Neebish Island. Once we reached the northern tip of Neebish, we turned and headed south through the rock cut, an engineering marvel.

Rock Cut – Neebish Island

Squeezed between the United States and Canada is Neebish Island. “Neebish” means “where the water boils.” Islanders tell stories of how their ancestors used to walk over the rocks to the mainland on the western side of the island.

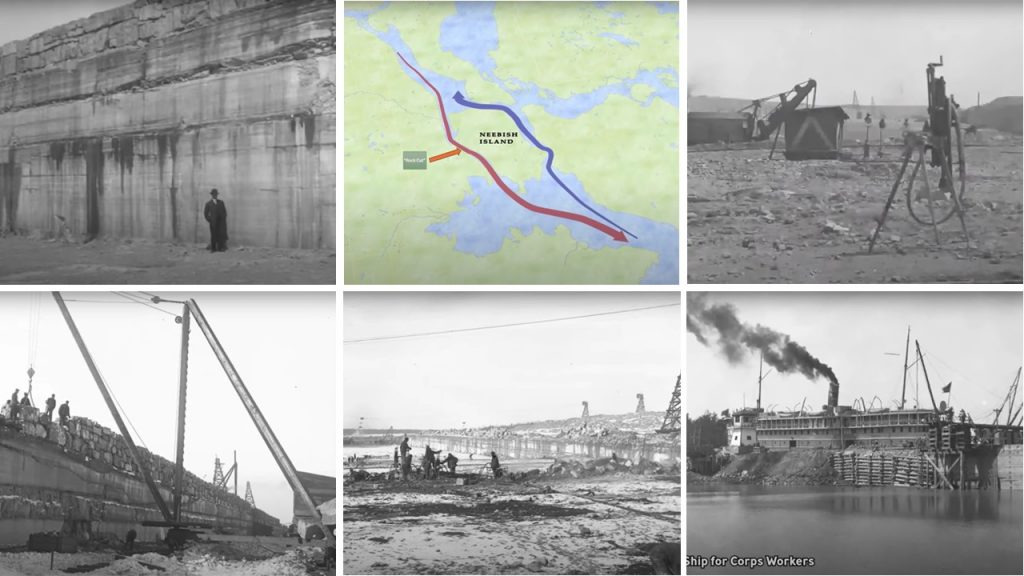

Rocks had surrounded this island with only a narrow shipping lane on the eastern side. Today, nearly 90 residents observe ships going northbound on the east side and southbound, through the ‘Rock Cut,’ on the western side. How was this rock cut made?

For two years, these men lived aboard a ship docked on the eastern side of the island (bottom right) while they built the “rock cut.”

Map Credit: Chuck Hayden Photo Credit: Army Corps of Engineers

This ‘Rock Cut’ is an engineering marvel, like the Soo Locks, yet there aren’t any gift shops. It all started in 1899 when the Houghton had collided with a barge in the narrow, eastern-side shipping lane. This accident had blocked all the other vessels for days. At that time the western side of the island had been impassible due to an outcrop of rocks.

An improved shipping lane would need to be built! Men from the Army Corp of Engineers labored for two years while living aboard a ship docked on the opposite side of the island. After using over 1,000 tons of dynamite to blast through 1.6 miles of rock, the southbound channel opened in 1902.

Islanders keep an astute look-out for ships, especially the Edwin H. Gott!

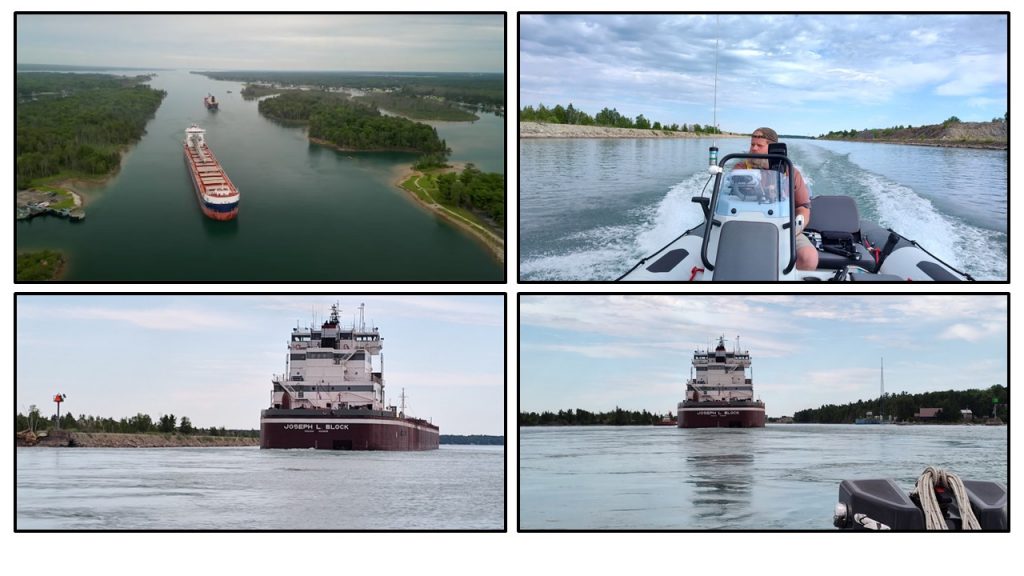

We shared the Rock Cut with the Joseph L. Block. Being so close, the ship reminded me of a skyscraper floating on its side through the channel.

Freighter Wash

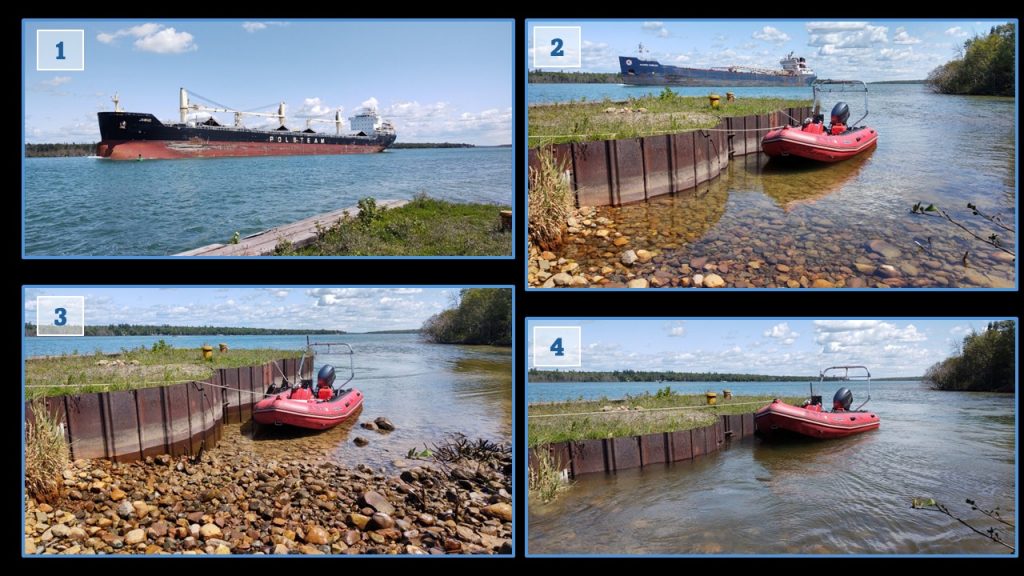

Have you ever heard of “Freighter Wash?” I hadn’t until our last trip to Neebish Island a few years ago. It is stunning and powerful. With Neebish Island’s narrow channel on the east side, it’s a perfect place to experience “Freighter Wash” also known as “Bernoulli’s Principle.”

Notice how the water level changes as the ships pass.

As a ship enters the narrow channel, water is drawn toward the enormous vessel to displace its weight. Along the shoreline, the water lowers quickly. It stays this way for several moments, but once the ship has passed the area, the water rushes back to shore creating a current that some cannot escape. Sadly, “Freighter Wash” can be deadly.

Another point of interest around Neebish Island is the Coast Guard Lookout #4. It is the last one of its kind.

Coast Guard Lookout #4

There had once been seven Coast Guard Lookout Towers placed along this shipping route. Men standing in these towers would relay information by phone to the next tower as well as the Soo Locks about “upbound” and “downbound” ships. If a problem should arise, the Coast Guard would be ready.

Today, there’s a group of dedicated individuals who are working to preserve this last Look Out Tower. Their next meeting will be at the Bruce Township Library on September 20, 2025 at 2:30. Their Facebook page is “Shipmates of Lookout #4.”

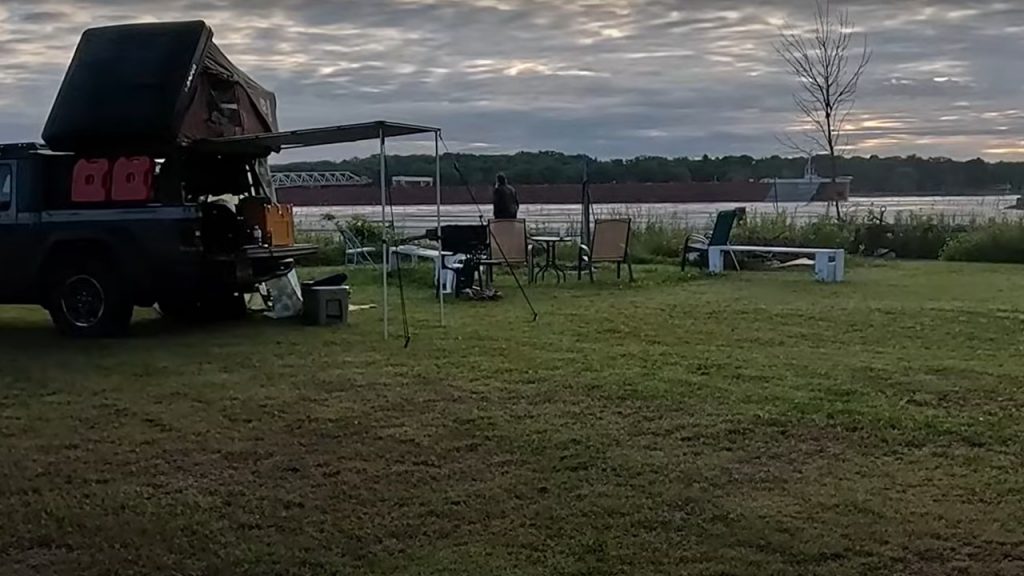

Camping With Freighters

We camped along the river, just north of the Neebish Island ferry dock. As the sun nestled into the clouds and our campfire crackled, a ship slid by us. What a peaceful view!

The next morning we folded our rooftop tent and secured our life vests. Our next stop was Sugar Island in search of Governor Chase S. Osborn’s estate, a man who deserves to be remembered.

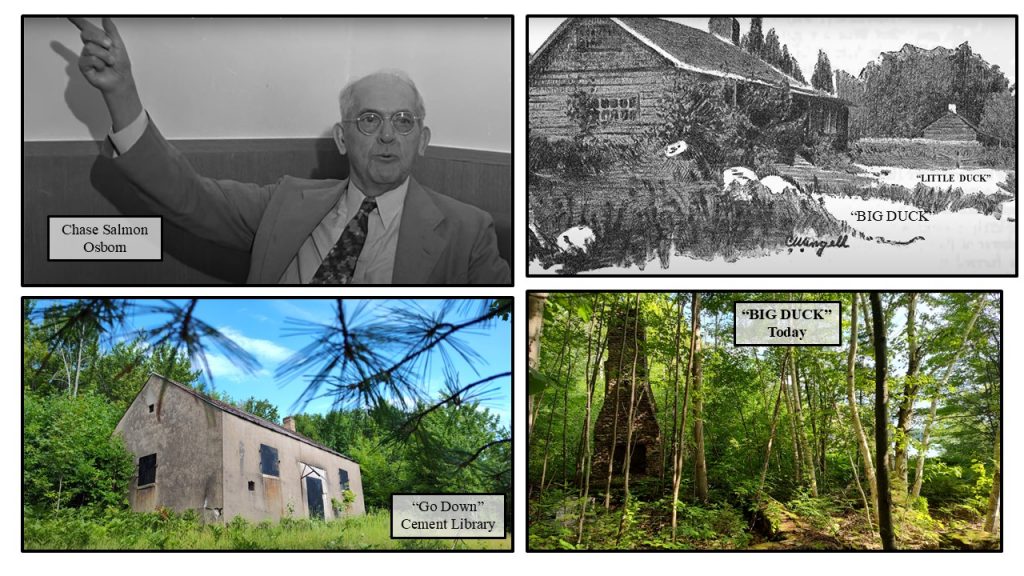

Sugar Island – Governor Chase Salmon Osborn Library

Born in 1860, Chase Salmon Osborn had embraced many facets of life. As a journalist, postmaster, author, businessman and 27th Governor of Michigan, Chase S. Osborn has left a permanent mark on our state.

As we rounded Sugar Island, his cement library came in view. Securing our boat to a tree, we hiked a short distance and found the foundation and chimney of “Big Duck,” the Osborn family cabin.

After loosing most of his writings in a fire, Osborn had built a cement library on Sugar Island, which he called the “Go Down.” As part of his quiet, wooded refuge, Chase S. Osborn had built “Big Duck,” a family cabin, and “Little Duck,” his workshop for pondering and writing. A full article about this eclectic leader is below under “Related Links.”

After a short stop at Sugar Island, we untied Sea Raven and headed in the direction of Sault Ste. Marie and the Soo Locks. Cloud cover drifted over us and soon rain began fall.

Sault Ste. Marie

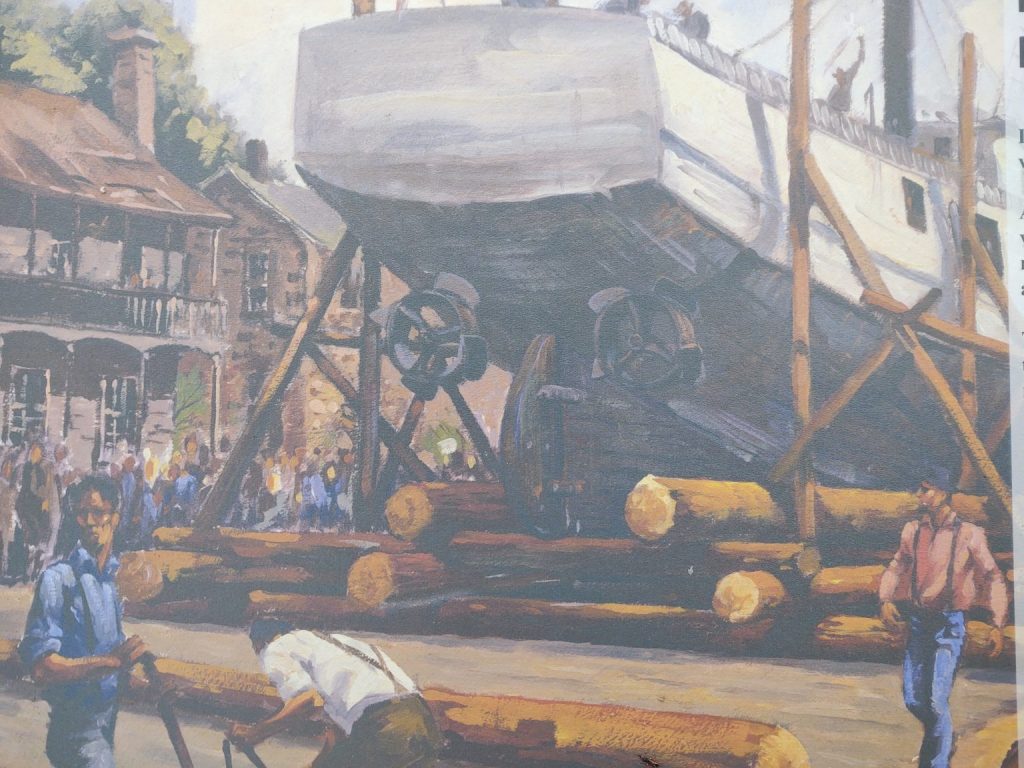

Sault Ste. Marie had been known as “Baawating,” meaning “the place of the rapids,” with a single community built on each side of the river. Then, in 1668 the French settled in the region making this the first ‘city’ in Michigan.

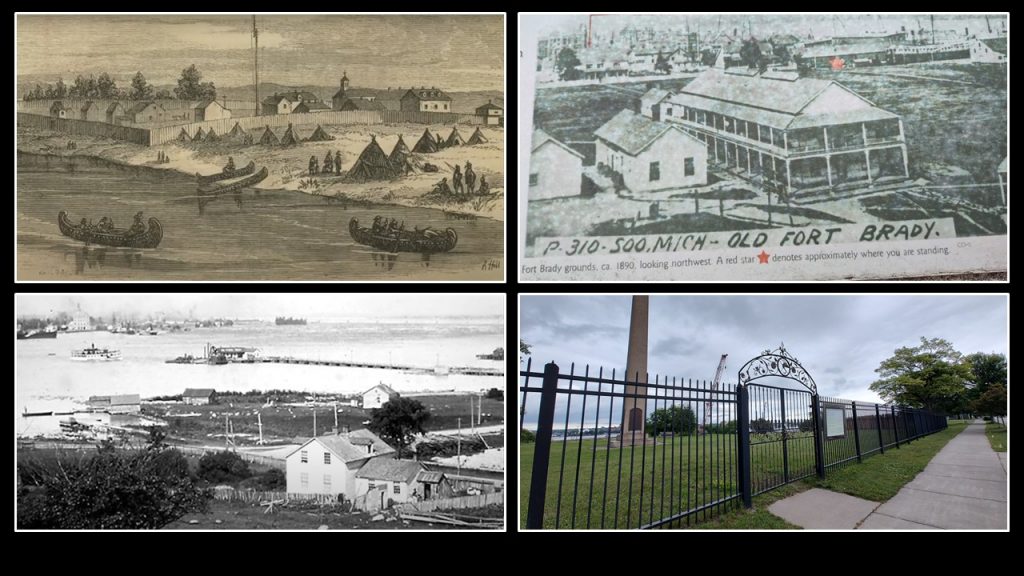

Sault Ste. Marie had been home to Fort Brady, a military post.

Fort Brady

Colonel Hugh Brady led troops to Sault Ste. Marie in 1822. They built Fort Brady along the shores of the St. Mary’s River to protect this vital trading route.

Later in 1893, Fort Brady was moved up on a hill overlooking the locks. This had been called “New Fort Brady.” When this new fort was decommissioned in 1944, the buildings became Lake Superior University.

Back on the river, we came to the Soo Locks!

Soo Locks

Making the Sault Ste. Marie’s shipping lane easier to navigate, the Army Corps of Engineers went to work and constructed the first “Slate Lock” opening in 1855. While this is an amazing feat of engineering, I was fascinated to learn that the first “door locks” ever constructed had been six thousand years ago in ancient Egypt.

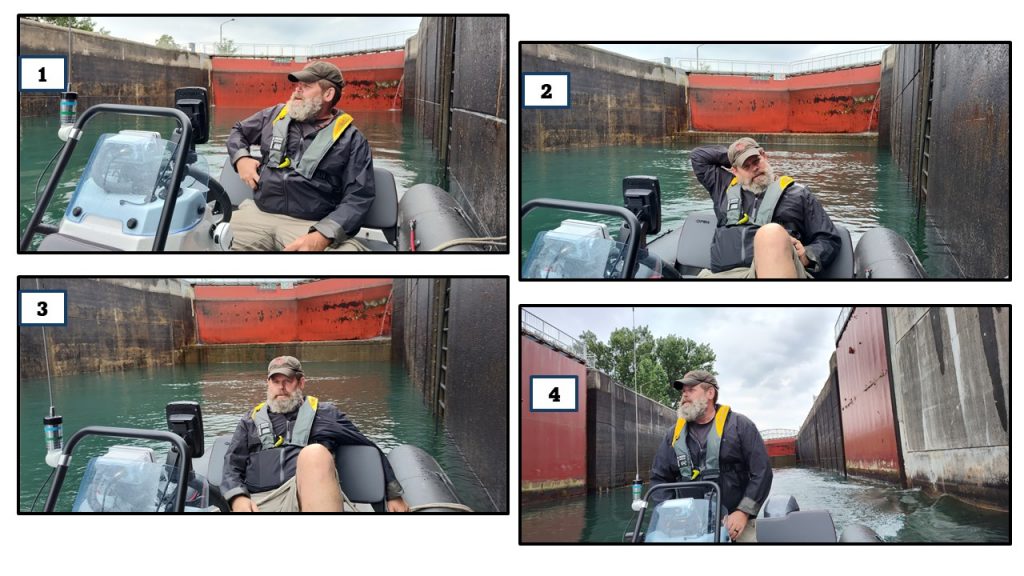

Today in Sault Ste. Marie, there are two sets of locks. One is on the Canadian side and the larger, commercial locks are inside the American border. Previously, we have always used the Canadian side to lower or raise us the 21 feet between the St. Mary’s River and Lake Superior.

making it easy to secure ourselves during the vertical ride.

Chuck was casual about traversing the locks, due to the amount of times he’s led groups of kayakers through these waters. For me, well, I kept a tight hold on the rope as this experience is still new to me.

As we entered the waterway, we were startled to see a United States Coast Guard helicopter circling.

United States Coast Guard Training

We studied the USCG helicopter and surrounding area, thinking there may have been a problem in the region. But we soon discovered the Coast Guard was practicing raising and lowering a liter, a basket to carry injured people.

We rounded the Coast Guard at a safe perimeter. As the mist became rain, we headed back toward the locks.

American Locks

“Look. The American side is open.” Chuck eyed the opportunity. “I’ve never gone through the American locks. . . Do you think . . .” He picked up his radio which was already set to Channel 14. “WUE-21 (Lockmaster call sign) this is Sea Raven, over.” “This is WUE-21, go ahead.” came the response. Chuck requested, “We are Sea Raven, a 16 foot zodiac. Could we lock through?” Chuck’s eyes shifted expectantly. “Come all the way in. We’ll toss you a line.”

Excitement effervesced as Chuck motored us inside the concrete tub. At our age, firsts don’t come along often. I tried to be suave and cool as the lock worker tossed me a line. I almost caught it. Chuck handled the line like a pro, winding it as we climbed upward and then handing it off to the lock mate.

As we came into view, people on the observation deck called. “Look at that tiny boat!” They pointed and captured the moment with their phone. “You’re not a freighter!” They jeered. “You got any beer?” Someone asked. “We’ll give you our beer!” Some else answered. It was jovial fun as they snapped pictures of our tiny vessel in the huge lock.

The Soo Locks welcomes over 7,000 vessels annually hauling over 80 million tons of cargo. We were so fortunate to have the chance to feel “big,” like the skyscraper-sized ships.

Being witness to the St. Mary’s River, which works harder than any other waterway I know, has been an incredible 74 mile journey! I am forever thankful for my husband, Chuck, who is constantly curious and courageous when creating these capers! Stay curious and make memories!

Related Links:

Join us on our St. Mary’s River journey in this YouTube video.

The Edwin H Gott – Restless Viking article

Lime Island’s full story – Restless Viking article

The Dangers of Freighter Wash – Restless Viking article

News 9 & 10 “Lookout Tower #4” report

The Secretes of Neebish Island: Islanders – Restless Viking article

Pine River Canoe Camp: Neebish Island – Restless Viking article

Chase Salmon Osborn – Restless Viking article

Soo Locks – Restless Viking article

Resources:

Drummond Island Tourism Association website

Pure Michigan Soo Locks Facts article

“A Landing Day” blog with maps of Drummond Island and the St. Mary’s Channel

Michigan.gov “Lime Island State Recreation Park” information

Ebay