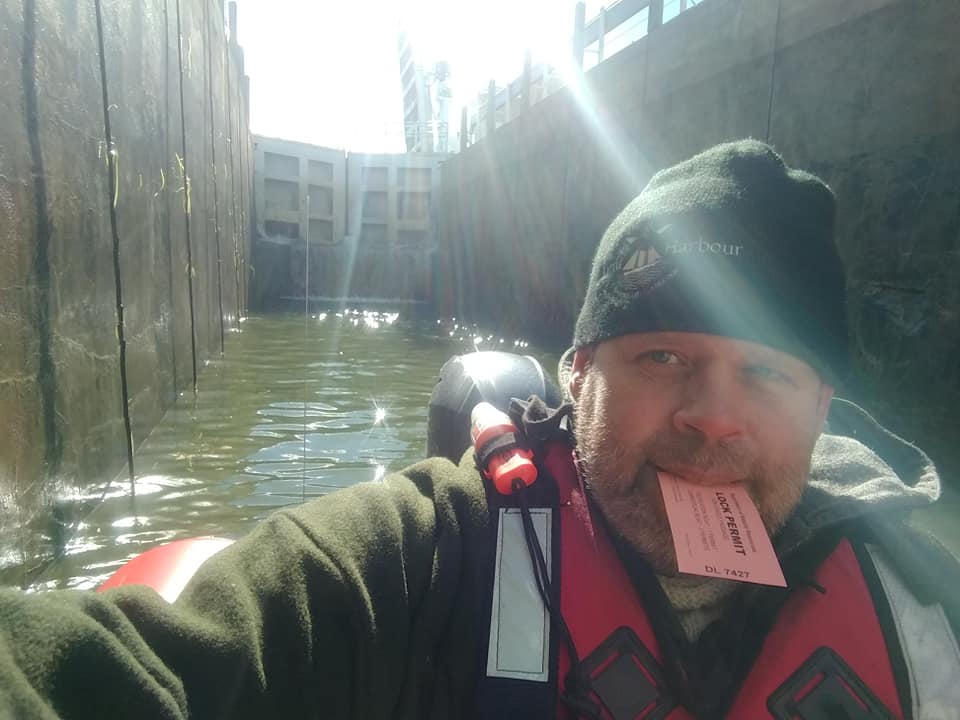

The wispy mist slowly curled up from the coffee-colored water. The crispness of the air was refreshing but hinted at sharp discomfort. We were layered up and warm, but this was just beginning.

The milky swirls slowly parted as a hulking steel corrugated scoop came into view. The bottom suddenly lifted out of the water and small showers of dribbling water noisily drained from the gate. One by one, the water dribbles retreated to the sides and faded. A red light turned green and that was our cue.

A grey shape exited the door of a small brick building beside the lock. The figure stood still with his hands in his pockets, quietly watching us. The green traffic light to the right dominated the morning.

The 4-Stroke Yamaha Outboard barely made noise, except for the water jetting from the cooling system.

“Morning. . . “, the lock master said with a high, raspy voice. We were still 40 yards away, but his quiet voice carried far across the calm waters.

“Morning”, my son, Noah, and I said in unison.

The steel scoop hung above our heads as water drops fell. Then it quietly descended behind us. We were in “the lock”.

As the gate settled behind us, I asked, “How much?”

“Ten dollars”, the lockmaster responded.

Noah was completely covered in a few layers of clothing, his hood and face mask covering everything but his nose. Even though I couldn’t see his face, I knew he was looking around with a calm, discriminating eye.

I handed the lockmaster a $10 bill. He disappeared into the brick building for a moment and returned with a ticket.

“You guys coming back today? We close for the season tomorrow.” He said with cheerfulness.

“Nope”, I replied, “We might hit the big lake and take out tomorrow.”

“Oh” he replied. “OK”. As if that isn’t something we should do.

He disappeared into the building and the other steel gate, in front of us, began to rise. He came back out and said, “Good luck. . . looks like a nice day.”

“Yep”, we said in chorus. I added, “Real nice. . .”

And so it was, we began our journey across northern Michigan by boat. We just passed through the first set of locks of the Inland Waterway near Alanson, Michigan.

The Inland Waterway is a historic waterway with a long and busy history. Waterways like this are a great way to see the land. . . or water. It is like travelling through the backyard of industry and neighborhoods. You get to see behind the proverbial “Curtain of Life”. Roads get all the attention. Our journey was quiet. . . surreal and very different.

We were travelling the entire waterway as late in the season as possible. The locks would close tomorrow and soon the water would slow and then turn solid. Everything would change and fall asleep until spring.

We were alone. All the slips at the marinas dotting the route were empty with a few dangling lines and the occasional fender swinging lazily in the crisp autumn air.

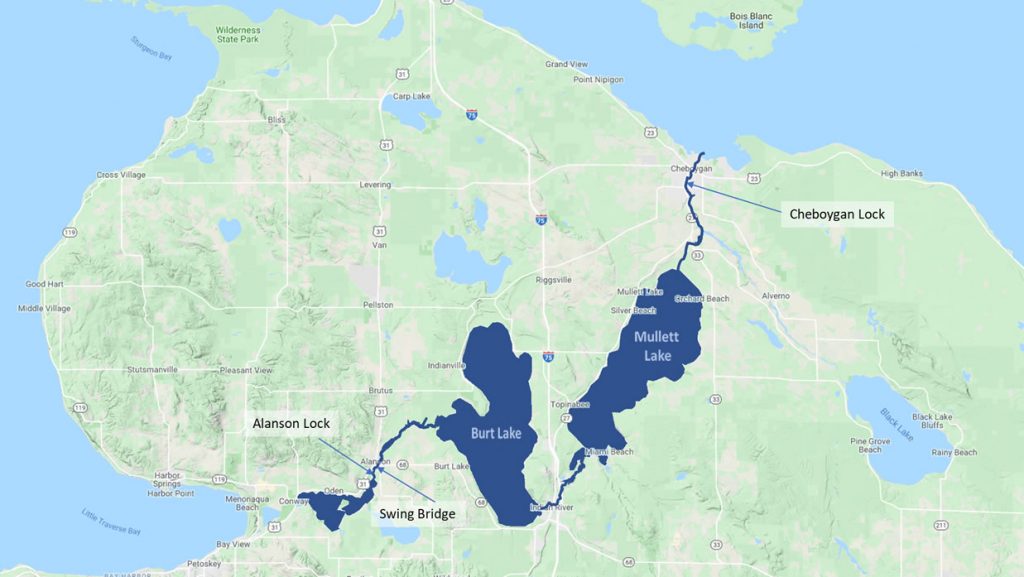

Michigan’s inland waterway is a 38-mile navigable water route (42 miles depending on where you start) that almost joins Lake Huron and Lake Michigan. Its history dates back millennia when local native tribes chose to navigate the calm waters to the other side of the great peninsula instead of battling the strong surf of Waugoshance Point and the Mackinac Straits. Indeed, over 50 native encampments have been discovered along the route, including a camp found near Ponshewaing which dates back 3,000 years.

In 1869, the lock in Cheboygan was built. In that same year, the “Cheboygan Slack Water Navigation Company” began passenger and freight service along the route.

In 1873, when lighthouses, wharfs and towns were being built at a fevered pitch in Northern Michigan, the Grand Rapids and Indiana Railroad reached Petoskey. As passengers and freight arrived, the waterway began to develop.

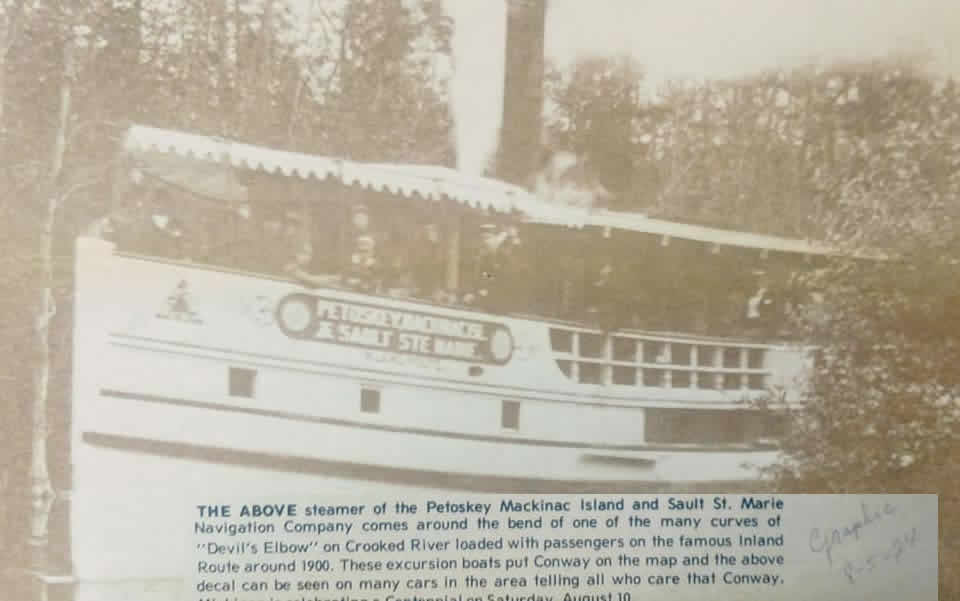

In the early 1900’s, the “Petoskey, Mackinaw Island and Sault Ste Marie Navigation Company” (being the creative naming geniuses there were) allowed passengers to take a steamer from Alanson to Sault Ste. Marie for about $3.00. From many stops along this route, you could grab a connection that would take you virtually anywhere.

In the 1920’s, when prohibition confined our nation’s drinking habits, the inland waterway served bootleggers from Lake Huron to the speakeasies of northern Michigan. A fifth generation summer resident, Mike, relayed a story of such rum-running adventures.

Apparently, on quiet weekdays, a local marina owner named Marv would take Mike’s great grandfather’s boat named the “Bar-Jo”. The Bar-Jo was left at the cottage dock in Topinabee while the family travelled back home to run their grocery store in Ohio. Marv would hop in the boat, cruise through the locks and power up onto Lake Huron. Once on the big lake, the registration numbers would be covered and the boat would speed off to Cockburn Island, a Canadian Whiskey drop point. With darkness falling, Marv (and accomplices) would pick up some hooch from some enterprising Canadians, pay the price and race back in the powerful 24′ Chris Craft. . . under the cover of darkness.

Upon arriving at his marina, just before dawn, he would promptly cover the boat in tarps, take it out of the water and wheel it way in the back of the marina shed – like it had been there for weeks. Then. . . they would wait. . . boat on a rack – whiskey in the bilge.

Later, the contraband would be “redistributed” and make its way up the waterway to the various “violators” and speakeasies. The BarJo would appear back at its dock, with a small cache of “spirits” tucked away on board as “payment”. Truly, there are some stories to tell here. We’ll get back to them at a later time.

But yeah, that was kind of the spirit that is the inland waterway . . . as Mike said, “They had the mentality of people that lived in a much younger America.”

As with all cool history, times changed. Railroads and roads spread across the state. New methods of transportation took demand from waterway transportation. The inland waterway fell out of favor with commercial traffic, but tourism and a few cheeky entrepreneurs kept things alive until today.

The world’s smallest swinging bridge (so claimed by the Indian River Chamber of Commerce) spans the waterway on River Street in Alanson. Boats up to 65 feet can fit in the locks, though the Crooked River will prove challenging for any steamer longer than 25 feet. The route is kept at a depth of 5 feet.

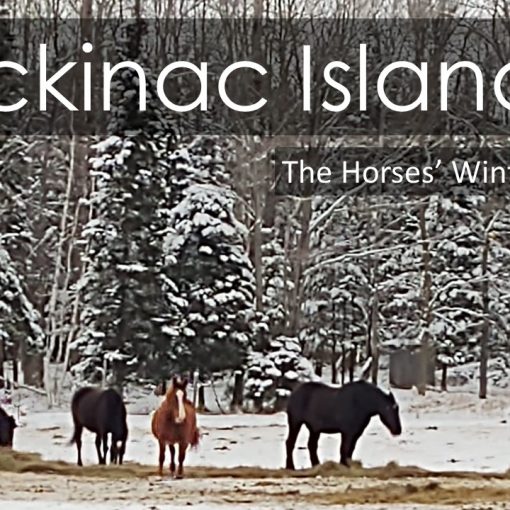

The route spans two counties, four lakes, three rivers and two locks. When the route abruptly ends at Lake Huron, you can head north for 15 miles to arrive at the tourist mecca of Mackinac Island. There is plenty of tacky tourist things to do along the way. Slurpy food, mini-golf, campgrounds, beaches, kayaks, paddleboards, blah, blah, blah.

After a couple of hours of idling and crossing some expansive lakes, we glided through Cheboygan. Just before the locks, we docked our mighty steed at the sea wall in front of the aged “Big Boy Restaurant”. We availed ourselves in the steamy goodness of the “all you can eat” breakfast buffet and called Mom (Poppins). She agreed to leave the comfort of her Mackinac hotel room and provide shuttle service back to the Jeep and Trailer. Noah took a nap at the public launch and ignored the Sheriff as the deputies took their boat out for the season.

If you have a boat or kayak, you may want to consider the Inland Waterway. It is busy in the summer and not busy in the early spring and late fall. At any rate, it is an interesting float – with plenty to see and a lot of history. Your pace will be leisurely, and your mind will be relaxed.