The mist rolled across the tiny fake village of Glen Haven. The enfolding morning fog was slowly retreating skyward as the sun burned it. I pushed the sticky door of the tiny “Park Ranger” office in the back of a newly reconstructed residence. The door squeaked open to reveal three, barely out of college, park rangers dressed in neat uniforms. A dry suit hung from the wall and the quiet office reeked of fresh paint and carpet.

They all looked at me with mildly startled expressions. Glen Haven was a new enclave of the Park Service. They had been busy the past few years rebuilding the small settlement. The plan was to eventually make a regular little interpretive village out of it. These guys seemed newly hired and enthusiastic federal agents with an air of structured confidence. Just the type of inexperienced people I wanted awkwardly inquiring further about my intentions.

“May I help you?”, one of them quietly asked. It was so quiet and their expressions were so similar, I wasn’t sure which one asked me.

“Where can I park for a couple of days?”, I asked eagerly awaiting their first question.

“Why do you need to park for a couple of days?”, the least experienced looking ranger inquired.

“Were heading to South Manitou.”, interested in what he would assume next.

“On the ferry?”, he asked.

“No.”, I retorted, hoping to plant a little frustration in his thoughts.

To my suprise, he ignored his own curiosity. He asked if we had park permits and courteously gave me some parking options. I was pleased by this. I immediately responded with my most charming thank you and began turning to leave.

“How are you getting out there?”, the most experienced looking ranger immediately demanded. I’m sure they could see my shoulders drop and a little sigh probably escaped my mouth. Here we go. . . I thought.

“Kayak.”, I responded while mentally preparing to deliver further responses with hints of sarcasm.

“We don’t recommend that visitors kayak to the islands” He responded in a practiced voice. It was the mid 1990s and kayaking to the Manitous was still a pretty rare event, but they probably received a few inquires.

“I know you don’t.”, I said withholding many options for a sarcastic comment.

He shrugged his shoulders, casually sat on his desk and looked at the floor. I wasn’t expecting that response. “Ok”, he said with a hint of resignation, “did you file a float plan.” He asked. I responded that we had. “With the Coast Guard?”, he further inquired.

“They don’t accept float plans for kayaks – at least in Frankfort.”

What followed were polished and formal warnings and inquiries trying to discourage me from doing something the park service considered dangerous, but had no authority to stop.

Finally, I took a deep breath, rolled my eyes and said, “Listen guys, I know the risks, I know the dangers. I know you don’t want to have to rescue us, but we don’t launch kayaks into open water with our fingers crossed, that isn’t how you do risky things. Thanks for being concerned and thanks for the recommendation for parking.”

Finally the experienced looking ranger said, “Understood. Well. . . let them know when you get there and let us know when you get back.:”

“Will do and thanks.”, I responded.

“Have fun and good luck”, he said.

This kind of thing happenes to me all the time. Professionally concerned park rangers are one thing. But as any female who hints at doing a multi-day solo hike will tell you, these unsolicited warnings come from everywhere (even people that have no clue) and they get old after a while.

That being said, I completely understand their position. There are plenty of people that attempt to do things they shouldn’t. Not because the endeavor is “too” dangerous, but because they aren’t prepared for the risks.

Just last week, a jet skier left a Marina in Grand Portage, Minnesota and embarked on a 22 mile journey to Isle Royale. This was despite warnings that you can’t operate a personal watercraft in a National Park and that such a voyage on mother Superior is not advised.

Fast forward to about 2020 hrs on Monday, July 8th and that same lone jet ski floundered in the foggy waters, out of fuel, with inadequate navigation equipment (or a lack of skill) and a location 22 miles off course, “south” of Isle Royale. Luckily, the “captain” of the jetski managed to catch a cell signal and transmit his emergency and coordinates to professional rescuers.

By 2220 hrs, a 689-foot bulk freighter, some knowledgeable mariners, some modern technology and a fair amount of luck conspired to locate the guy. Just before midnight, the captain and jetski were rescued by the freighter. You can indulge in a well researched version of the story here.

You take my point, this jetski story is the reason for the prepackaged “We do not advise that” speech. Authorities have, often, had to deal with people like this jet skier, who launch themselves into risky adventures with their fingers crossed. Unfortunately, these situations sometimes come with tragic results. Nobody likes to deal with it. I can assure you, it’s no fun recovering the lifeless body of an adventurer who failed.

I’m also here to tell you, even as a professional rescuer, I still encourage risky adventures. For sure, life would be much less rewarding without these epic undertakings. Getting far from our comfort zones to do mighty things. It is one of my “raison d’etres”. Truly, I don’t want a life without epic adventures.

But, you don’t just cross your fingers and head off into a milky vapor shrouding a huge blue expanse of water. That isn’t how we do risky things – and survive (or save ourselves the embarrassment of a midnight rescue 22 miles off course from a 22 mile journey).

This same weekend, I also embarked on a 33 mile (one way) open water journey in a watercraft only a couple of feet longer than the jet ski. But, I returned to my launch (68 miles later) with enough fuel to do it again and without any hint of incident.

It’s real easy to do. Plan for the worst, hope for the best. Two is one, one is none. Have contingencies, have reserves, bailouts, blah, blah, blah. For some, it seems daunting to plan such risky adventures, but it is pretty easy.

Here’s how.

P.A.C.E yourself. . .

I’ve only discovered the PACE Mnemonic in the past decade. Truthfully, it would have been very helpful to use such a method for many of my past “fingers crossed” adventures that turned ugly. PACE is a way to “think like a Green Beret” to borrow the expression from the military. I first learned about PACE in an Army Field Manual dated March of 2009 and it was meant for communication plans. But honestly, it can be applied to all sorts of planning.

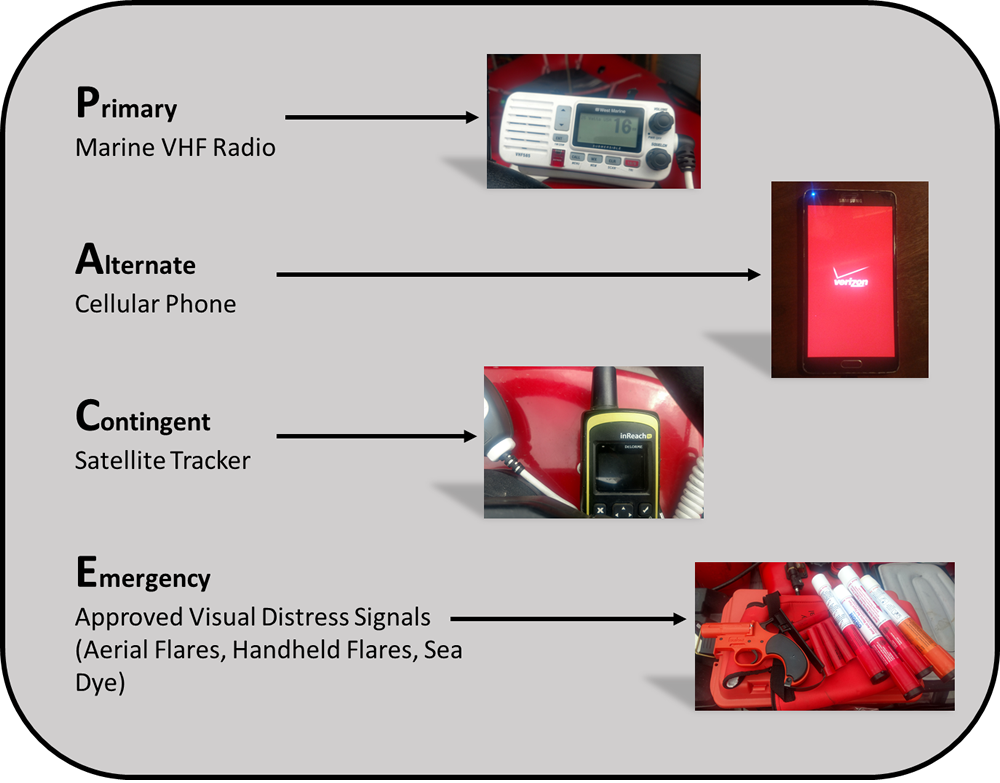

The PACE methodology (when used to build a communications plan) is an acronym that stands for “Primary, Alternate, Contingency, and Emergency” means of communication. The method requires that you determine the four best forms of communication and the order you will move through those methods to establish contact. Each method should, ideally, be independent of each other.

For instance, an open water expedition might have a PACE Communication Plan that looks like this:

In this example, the primary means of communicating would be Marine Radio. It is monitored by the Coast Guard, most other vessels and marinas. It is reliable and allows you to listen to other vessel traffic and even receive marine weather forecasts. The VHF radio represents the most efficient , effective and routine method of communication.

A cell phone would work for contacting the Coast Guard, marinas, towing companies and for assistance. It can also be used to receive weather reports and other news. If your VHF radio system fails, your smartphone can be used as backup. The Alternate is another common method of passing a message, but normally not as efficient as the primary means. It is often used in conjunction with the primary means.

The Satellite Tracker can receive spartan weather info, but can also provide two way communication with certain parties. It isn’t as comprehensive as the Primary and Alternate means, but will work in a pinch. It is not normally as convenient or efficient as the first two methods, but is capable of passing traffic when necessary.

An Emergency. Everything else fails and most likely you are in trouble. Flares, smoke, dye and visual signalling will work in a maritime emergency to call attention to your situation. It is a last resort but can be effective in calling for rescue. This method usually sucks, but is capable of limited communication.

The PACE plan doesn’t provide frequencies, phone numbers, contacts, etc. That is outside of the scope of the plan. It is, therefore, important to be very familiar with these forms of communication and to be trained on its use and have established knowledge with whom to establish contact, how to use it and the system’s capabilities.

Essentially, a PACE plan (plus training and knowledge of each system) provides you with a plan A, B, C and D. Plan D is typically used when the worst possible situation has happened. When the worst thing that can possibly happen, happens. . . then take hope, because things can only look up from there (usually).

While PACE is a great methodology for communications, it stands as a great methodology in planning for high risk endeavors. From watercraft propulsion systems, food supply, mode of travel, medical and first aid care, it is a system to use for planning. . . potentially. . . everything. It organizes plan A, B, C and D in a logical order.

Let’s toy with this idea for a minute:

Food

Primary – Fresh fish, meat, milk, etc from activities, local populations, restaurants in villages

Alternate – Canned and dehydrated food

Contingent – Resupply, MRE, Snack Food from Vehicle

Emergency – Emergency rations, local flora & Fauna, fish traps, bugs, grubs

Watercraft Propulsion

Primary – Main Outboard Motor

Alternate – Kicker Motor

Contingent – Improvised Sail and Rudder

Emergency – Paddles or Tow by other vessel

Route Planning

Hikers of long distance marked trails or kayakers of major rivers will find this methodology a little overkill, and they should. This type of planning is best used for those situations where your personal safety and survival is solely up to you. Long distance open water crossing in small craft – like a jet ski, hiking the uninhabited coast of Nunavut or Alaska, uninhabited island camping, moving through the canyons of Afghanistan, the jungles of central America or the coast of the Arctic. These are places where PACE is helpful.

In summary, use PACE as a tool for those risky things you do. You can get lucky and your “fingers being crossed” plan works just as you thought it would. I have had those days and I see many adventurers burning luck to survive their foolishness.

No matter how smart you are or how hard you work or how well you plan, reality always gets a vote. Mike Tyson (one of the world’s foremost motivational speakers and philosophers) once said, “Everyone has a plan ’till they get punched in the mouth.” Which is to say, if you burn your luck to survive, your day is coming.

If you’re like me, you’ve been punched a lot. Have a plan for it. Expect it. Then your chances of success are much better.