This is a continuation of the “Desert Expedition” report. In our first dispatch, we talked about Wupatki and the mysterious abandonment. We considered the evidence, visited the ruins and the road led here. The heart of the Ancestral Pueblo civilization.

See Wupatki – The Shadowed Village

As I strolled around the backside of Kin Kletso, I noticed a tiny sign high up the rock face that said, “trail”.

“Wait”, I thought. “There IS a trail to the top of the canyon rim. . . I hope”. I picked my way thru some rocks and as I approached the canyon wall, I saw a few signs marking a zigzag of ascending, narrow trail that disappeared into a small slot.

I followed it, stepping lightly as the trail ascended the canyon wall, through the narrow slot and finally emerging on the expansive, flat mesa above Chaco Canyon. The wind howled past like a lonely witness. Tiny signs and cairns marked the way. I looked down onto Kin Kletso, a “great house” (apartment like structure) near “downtown” Chaco. I could see no one, except the crow perched on top of my Jeep a couple of miles away.

Kin Kletso, a great house of Chaco Canyon. Great houses had many rooms and multi stories.

It was an amazing view. The dusty expanse of the canyon parted the earth as far as I could see to the north. To the west, the canyon cradled the setting sun and a light haze added mystery to what was beyond. And to the south, Fajada Butte, the ancient observatory, stood as an ancient eminence in the southern canyon, miles away.

This is where it all happened. Chaco Canyon was the center of one of the most advanced cultures in North America and I could see why. The ruins at Chaco were large, prominent and inspired awe. It was expansive and it was imposing. It was remote and it insisted on a quiet, lonely reverence.

I came to Chaco from the south, turning off Navajo Service Route 9. I was immediately greeted with a warning, “Rough Road – May be Impassible”. It was a 44 minute drive to the visitors center across arid and desolate land. As I crested a particularly steep hill, I was suddenly greeted by the regal Fajada Butte. At that point, I realized I had arrived someplace special. I can see why the Ancient Pueblo choose this place.

The remains of a 95-meter-high, 230-meter-long ramp are evident on the southwestern face of the butte. The magnitude of this building project was obvious, without an apparent utilitarian purpose. The use as an solar observatory is under debate.

Chaco Canyon was the centerpiece of this excursion. It was central to thousands of people between 850 and 1250 A.D. and is a wonder of ancient structures and architecture. It is a master planned community of the most advanced culture of the United States (in the ancient world) and boasted the largest buildings on the continent until the 19th century.

But as we will see, the architecture is just a small piece of this amazing puzzle. The infrastructure, engineering, labor organization, reasons for its existence, advanced techniques and governance are incredibly complex. But honestly, what makes Chacoan culture so interesting, is so much we can’t figure out.

But, let’s start with some architecture.

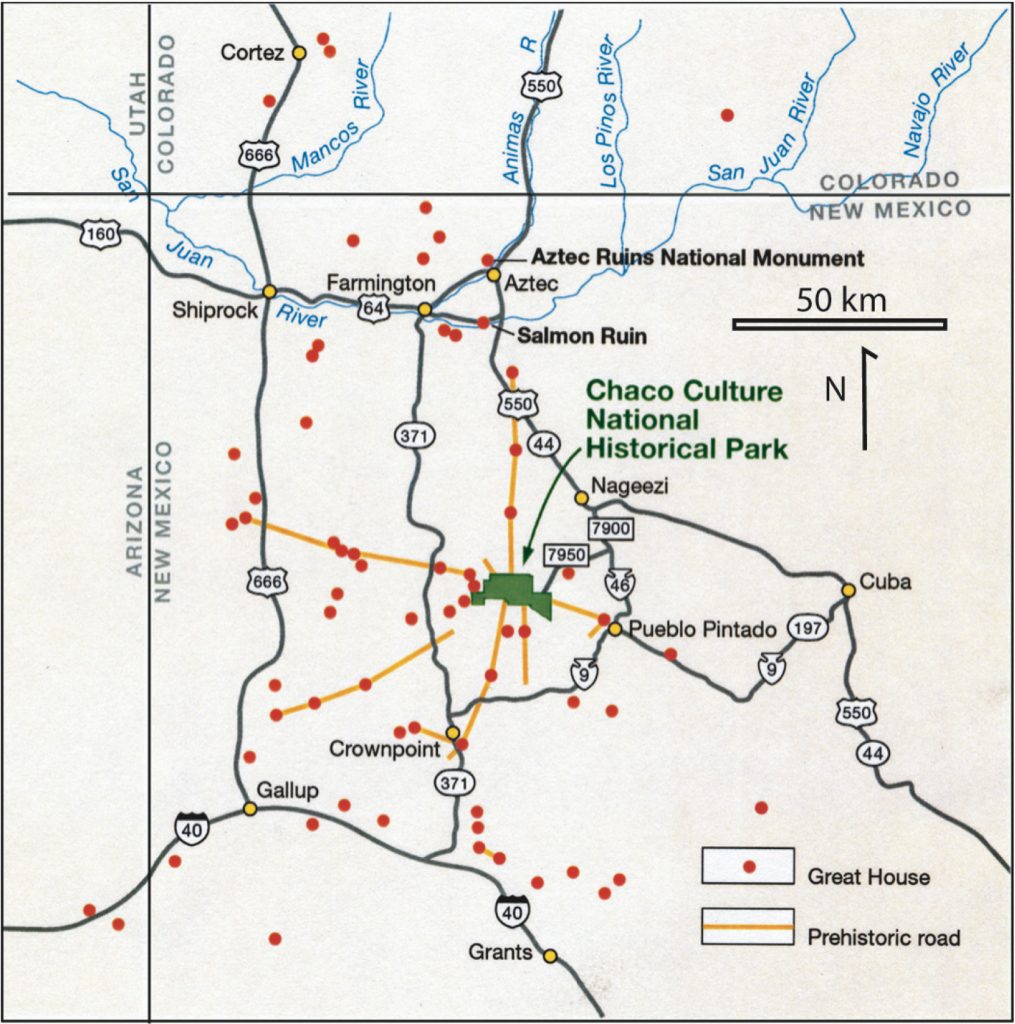

The crowning achievement of Chaco Canyon seems to be Pueblo Bonito. Pueblo Bonito is one of almost 200 “Great Houses” of Chacoan Culture and the name means “beautiful town”. From a modern point of view, it is pretty amazing.

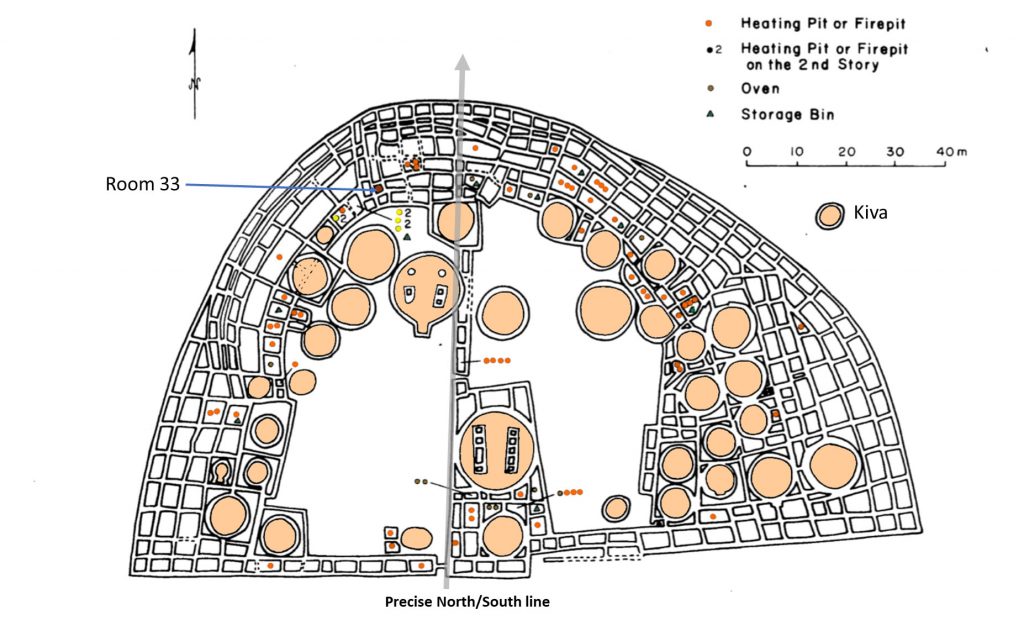

The building sprawls across 3 acres with a half circle shape. Its center courtyard is split by a very precise north-south line. Walls that are 3 feet thick in places, were built to accommodate 4 to 5 stories. At one time, Pueblo Bonito was thought to house a thousand residents in over 800 hundred rooms.

Unlike many sites throughout the southwest, which were built in a single season, many Chaco Canyon Great Houses were built over almost 80-100 years. In fact, they took an immense amount of planning and a staggering number of person-hours to build. Pueblo Bonito is estimated (the highest estimate) to cost almost 800,000 person hours. To give that number scale, that is over 400 full time workers on the job for a year. That’s about the same labor it takes to build 180 modern single family homes. Truly, these great houses are pretty spectacular.

And that’s just one great house. There are over 4,000 archeological sites in the canyon including 15 great houses and hundreds of other outlying structures. Even the National Park Service admits it doesn’t know exactly how many structures existed, but there are many. So many, that it was first estimated that the canyon had well over 10,000 inhabitants. But recently, they have drastically lowered that estimate to less than 2,000. . . and there is where it “starts” to get interesting. Pueblo Bonito itself is now believed to have housed only 60 people, not the near 1,000 it was first assumed. But, we’ll get back to that.

Right now, I want of offer a bit of a thorny question. . . how did the builders and designers follow the plans for these great house structures? It took decades to complete and no ancient culture in North America had a written language. How did they pass the plans for the great houses over decades? Even further, who organized such a major undertaking? There were probably hundreds of workers involved in the building of just one great house over almost a century. Who were the supervisors for this project? And if the populations were so small, where did the thousands of workers come from? You get my point, of course. Things aren’t adding up.

But, let’s not stop there. Resources would have been another major problem. In order to understand this next point, we have to get a little science-y. To study the timber resource situation of Chaco Canyon, researchers had to use this seemingly bizarre archeological technique that analyzes “pack rat middens“. A midden is a debris pile constructed by rats that can preserve material [from that era] for up to 50,000 years. According to studies of these middens and the resulting wood waste contained in them, Chaco Canyon was deforested rather quickly. In the early days of Chaco, they cut the indigenous Pinon Pine, but ran out in less than a couple of decades. It is estimated that nearly a quarter of a million trees were used to construct Chaco Canyon and only a fraction of those trees came from the local area. Those pack rat middens have shown us that after they ran out of local trees, they had to drag them, by hand, from the nearby mountain regions of Chuska, Zuni and Mount Taylor . . . 50-70 miles away.

What’s even more amazing, archeologist don’t have the faintest evidence as to why they built great houses. These great houses didn’t really house many people. According to the staff archeologist I chatted with, most non-canyon sites in the southwestern United States have plenty of archeological evidence to support the “expected” population. But not Chaco Canyon, Chaco should have evidence of thousands of burials, but only about 60 exist for Pueblo Bonito. And a large portion were discovered in the mysteriously named “Room 33”. All of the great houses and structures were basically empty – except for a skeleton crew. And many of the resources were carried, by hand, from over 50 miles away. Stange eh? It gets better.

Chaco Canyon doesn’t have a lot of fire pits, sleeping areas, or areas for household chores that are normally found in residential dwellings, but what Chaco does have are “Kivas” and lots of them.

A “Kiva” is a pit constructed for various social purposes, especially for “religious” ceremonies. There are kivas of different sizes. Most are only big enough to fit a few people but some are enormous. In Chaco, there is an isolated Kiva called, “Casa Rinconada”. It is as big as any mosque or temple with a masonry firebox, inner bench, four roof-supporting large seating pits, masonry vaults, and 34 niches encircling the kiva. Unlike other Kiva’s it has a unique 39 foot underground passage.

Pueblo Bonito itself boasts 40 Kivas. One for every 29 rooms or every 2 residents. Of course, this begs the question. . . why?

Rituals and ceremonies are the best guess. But. . . and you’re probably used to this in our Chaco Canyon saga . . . we’ll get back to that.

Let’s talk about some recent discoveries at our little spiritual capital of the Anasazi. Actually, as amateur anthro-archeo-oligists, we’re supposed to call them Ancestral Pueblo. Anasazi is Navajo for “ancient enemy” and the descendants have asked to be called Ancestral Pueblo instead. After all, it is “their” name, so that’s what we will call them.

Anyway, let’s talk about something they are discovering more of every year . . . roads.

The most widely circulated number for Chaco related roads is 400 miles, but due to advances in technology, the past few years have increased that number to over 800 miles with more being found every year.. That is an amazing number if you consider Chacoans didn’t use carts or wheeled vehicles. The main roads are 33 feet wide (secondary are 15 feet wide) and extremely straight. They do not avoid obstacles. If the road met a cliff, they carved a stairway. If it met a mountain, they went over it. When the road had to turn, to branch off to another location, it was a sharp angle. No gentle curves in Chaco roads, straight and to the point.

Even more compelling is we don’t know “exactly” why they built them. They weren’t really needed at the scale and width they were built – for just “walking” on them. Although many of the roads lead to something, a large number don’t. They just kind of terminate for no apparent reason.

So yeah, add a few hundred miles of road that don’t make a lot of sense to our growing lists of mysteries. At least to our modern way of thinking.

The achievements of Chaco Canyon are pretty amazing for an ancient civilization. Those accomplishments would have been astounding if Chaco Canyon actually had a major population, but it didn’t. The sheer size of the work force suggests a complex leadership that could organize many large work parties including logistics, construction, trade, food, water and shelter. It is easy to see that workers came from surrounding settlements, but imagine the difficulty of organizing them. . . without mail, phones, or especially a written language. They built massive single great houses over generations. They over-built a sizable network of very straight roads, huge Kivas, and an observatory. All of this makes for a phenomenon that we are still trying to answer. But if you allow me, I would like to indulge in one final unknown.

One last mystery remains to be mentioned.

Around 1250 CE, people simply left. They abandoned Chaco Canyon, moved away, never to come back. Chaco remained abandoned until the Navajo found the ruins a couple centuries later. So, a society builds a massive, not populated, ancient, capital-like city with an outsized network of roads. This was a massive undertaking of labor, resources and management. They did this without a written language nor clear wealthy class. They keep it going for a couple of centuries and then they simply leave it behind and never build anything like it again. Clearly, this begs some speculation, debate and consideration.

Why did they leave?

Well, some scholars have confidently proclaimed it was because of climate change. A severe, 50-year drought just happens to coincide with the abandonment. It is in all the publications and research. The conclusion was that the drought must have dropped the water table so far they they couldn’t get water for farming. Of course, Chaco Canyon didn’t have a major population, but that trivia is often ignored. The water table was actually too deep for any reasonable access by ancient peoples anyway, so a drop in the water table probably didn’t matter.

In addition, the Ancestral Pueblo are known to have survived worse. Their corn varieties (still around today) are very drought resistant and their network of canals, rain catches and diversion techniques could probably overcome this major drought. In fact, a Hopi friend I made on the excursion (a descendent of the Ancestral Pueblo) mentioned that their corn would “save the world if climate change turned everything to desert. We have the only breed of corn that can survive.”

To drive this point home, within the 2014 Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences their is an article that reports. . . “after extensive review, the archaeological and environmental record failed to produce evidence of an event that was severe enough to cause the people to abandon their settlements”. This counterclaim was always a nagging side note to scholars, but visitors to Chaco are “still” told it was environmental stresses.

What has emerged now is a theory that, while the environment was a factor, something much more sinister was at play. “Social Collapse”. Which is inumberably more interesting to me.

But, we will get to that in Part II of the Chaco Phenomenon.

Interested in learning more? Do It. If you visit, you won’t be disappointed. And plan to stay a while. Chaco Canyon and Mesa Verde would be great additions to your list.

I hope you have found this interesting. I would be exceptionally curious of your comments, thoughts, additions and analysis below.

Kin Kletso

Computer Restoration of Pueblo Bonito

Interior Pueblo Bonito

Unique Corner Doors Pueblo Bonito

Pueblo Bonito

Kitchen Area – Pueblo Bonito

Kivas in the Foreground

Rear Wall of Pueblo Bonito with damage from Threatening Rock – a rock fall from the January 1941

Rear Wall – Pueblo Bonito

Kin Kletso

Ruins of an Ancient Staircase leading out of Chaco Canyon

6 thoughts on “The Chaco Phenomenon”

Very well written and extremely interesting! My curiosity and imagination are piqued, so I look forward to learning more. Thanks for sharing this experience with your readers.

Thanks Jim! The story kind of writes itself in this case.

Good stuff! Thanks for the interesting read.

Thanks!

I actually found your site because I wanted to see if anyone else suspected vikings to me the spiral signs on the walls that line up with the solstice looked exactly like ones I have seen on old viking trails as my ancestors I like looking at things they make and the round things I think you called Kiev looks like how they made there storage containers and they would follow lines of the sun amd moon to be sure to find there way back from where they came they were also known to burn there own people so I would imagine there slaves they left behind in room 33 so they would not have to feed them on the trip back they had gone that far and ancient enemy name seems more like what you would give a viking that would raid your land and people non stop for probably decades at a time I can see them leaving a crew behind and going and coming back time after time having a few buildings to change per night as to to not be dropped in on a party of rebels that want there people or stuff back from them I imagine they were what made the Indians who were known to be peaceful people unpeacful when later saw similar white men traveling again that way during the gold rush years would make much more sense as why they would attack people later if they had beeen though years of tourcher by viking raiding parties but just my point of view.