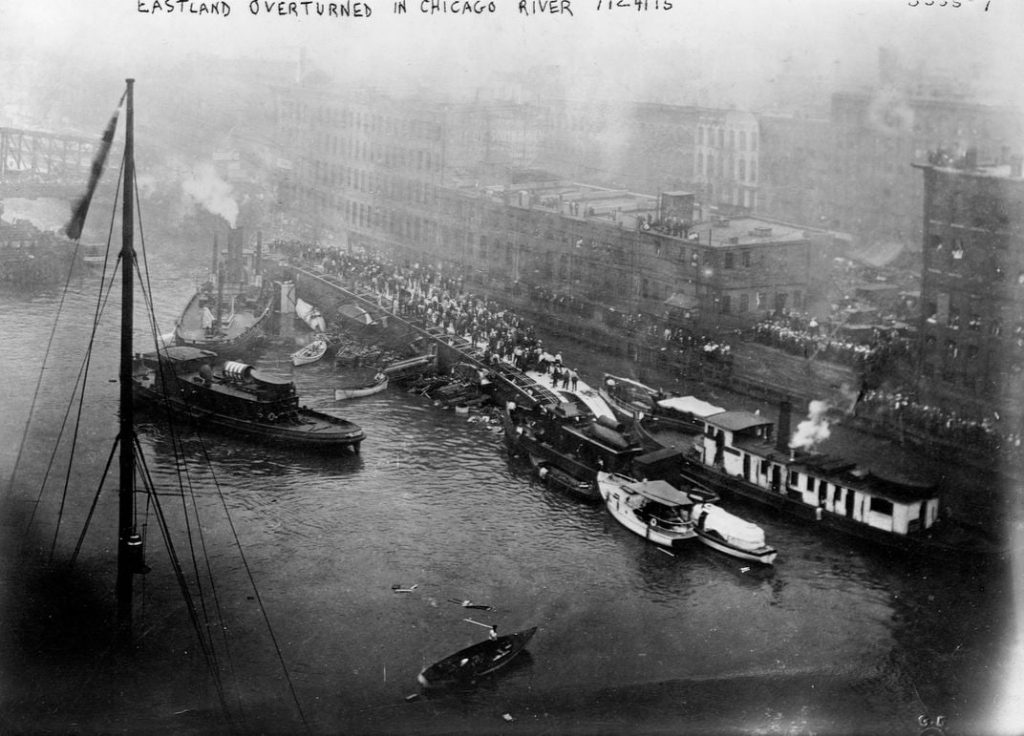

July 24, 1915 had been a chilly summer morning as people gathered at the Chicago River, preparing for a company picnic. A few minutes after boarding, the Eastland rolled onto its side. More passengers had died that day, 20 feet from shore in the Chicago River, than passengers on The Titanic’s sinking three years earlier. Honestly, I hadn’t known the details of this disaster until recently. Join us as we delve into the sad saga of the Eastland tragedy, the greatest maritime disaster on the Great Lakes.

Photo Credit: The Chicago Tribune

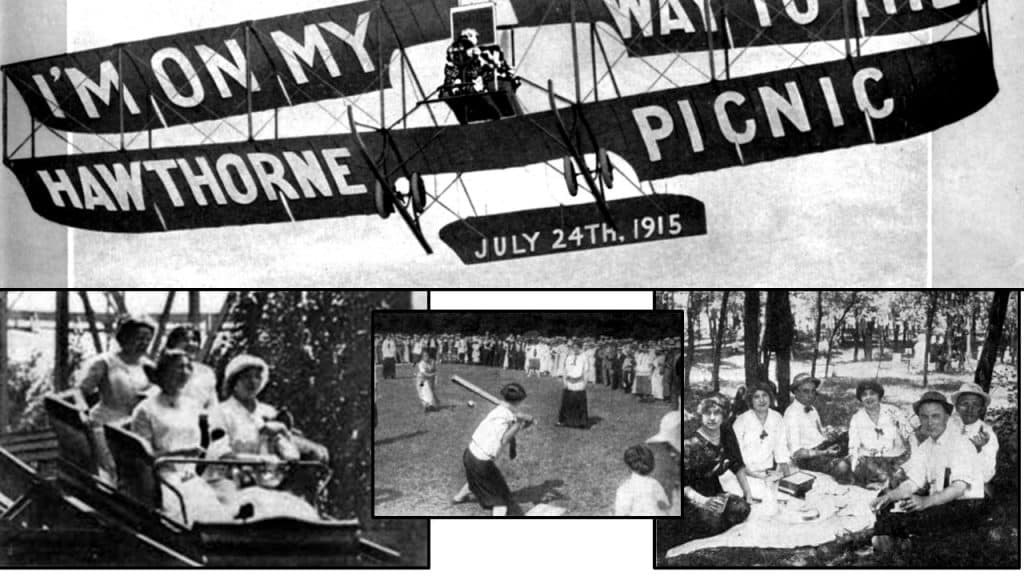

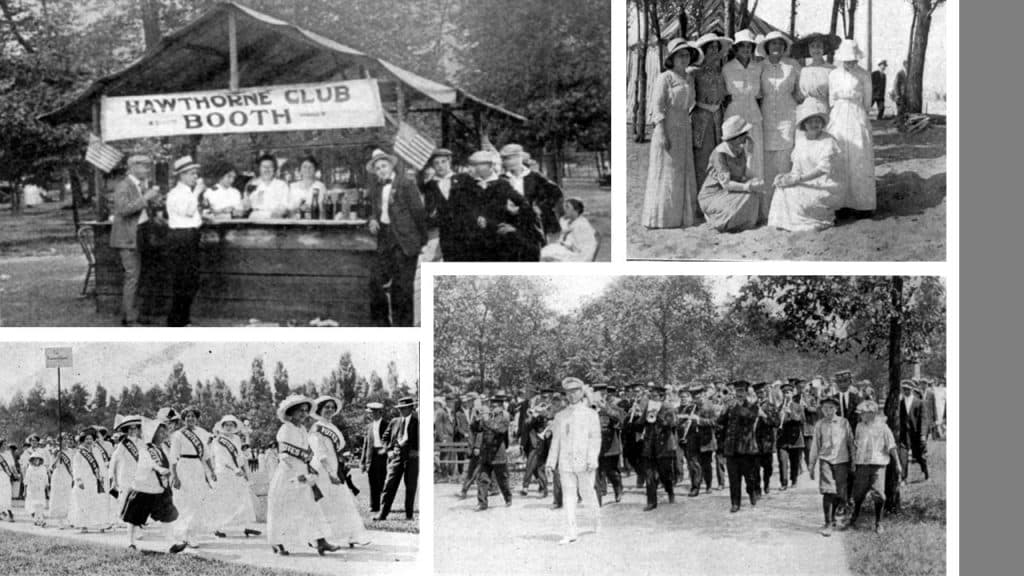

Hawthorne factory workers from Western Electric, along with their families, had bustled with excitement on the Chicago River docks. Seven thousand people had been waiting to board one of the five steam ships chartered to take them to the company picnic in Michigan City, Indiana thirty-eight miles away. Within minutes the day had tuned tragic.

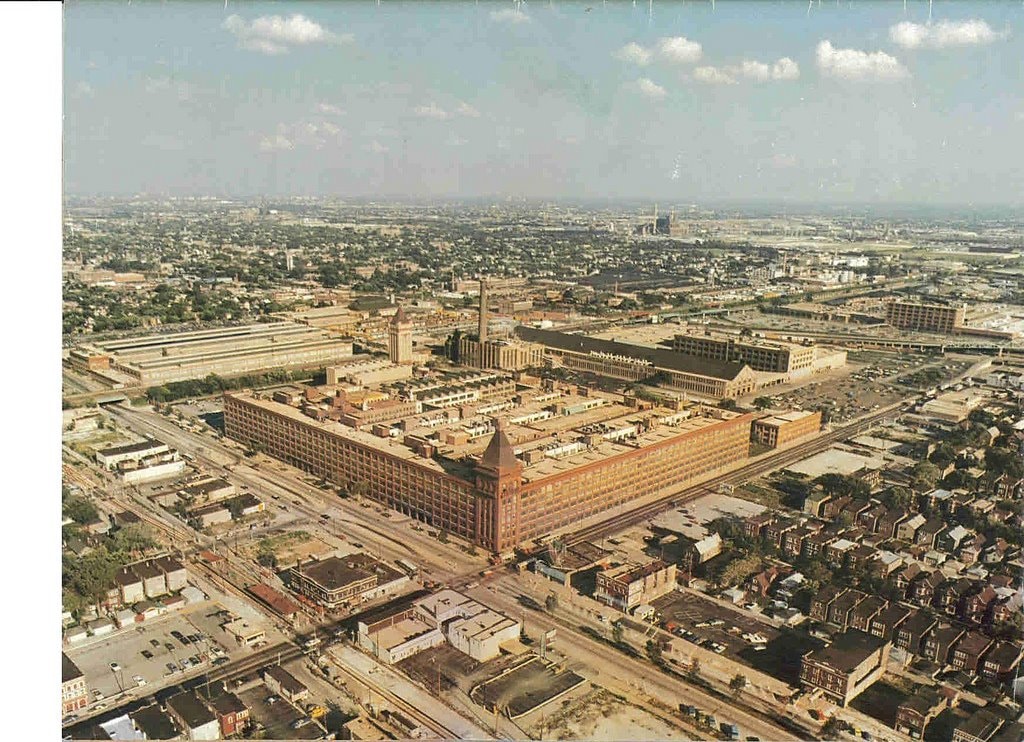

Why Did Western Electric Build The Hawthorne Community?

With uprisings at Western Electric downtown factory, the company had wanted a fresh start. They had soon secured land ten miles to the west of Chicago. Western Electric built a new factory, surrounded by a community of workers. This idyllic “town within a town” had everything the employees needed, thus curbing disgruntled displays. Most of these workers had been first and second generation immigrants from Czechoslovakia, Hungry and Poland.

Photo Credit: Industrial History

In order to break up the monotony of the six day work week, the Western Electric’s, “Hawthorn Club” hosted dances, concerts, ball games and the annual picnic.

Photo Credit: Eastland Disaster Historical Society

Each year the Hawthorn Club had set aside one Saturday where all the workers had the day off for a company picnic. Laborers paid $0.75 for passage on a steamboat to Michigan City, Indiana for a day of games, socializing and eating.

Now, with this picture of the Hawthorne workers’ lives painted, let’s return to the Chicago River on the day of the picnic. . .

Boarding The SS Eastland

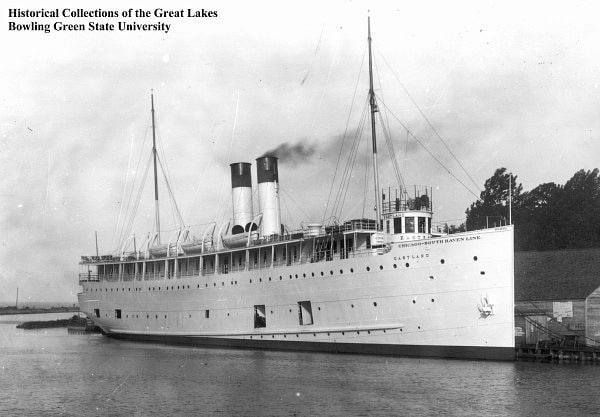

Photo Credit: Historical Collections of the Great Lakes

Bowling Green State University

Herman Krause, tall and lanky, had wanted to be “Uncle Sam” in the parade. He had been told to be on the first ship leaving for Michigan City so he could be in the pageant. Dressed in his red, white and blue suit, he had arrived early to secure his place in line.

Note: The women traditionally wore layers of long dresses, even in a casual setting. Men dressed in full suits.

Photo Credit: Eastland Disaster Historical Society

A thirteen year old girl, Bobbie, was excited to board the first ship, the Eastland, along with her mother, Maryanne and little sister, Solbay. Their Uncle Olaf had been escorting the three women for the day. Dressed in their finest, they had arrived at 6:40 am to find the best seats for their journey.

Photo Credit: Military History

Maryanne had stated that she “didn’t like the feel of the Eastland.” As the daughter of a Norway fisherman, Maryanne had a sixth sense for ships. As the boat leaned to starboard, toward the dock, she had stated firmly, “There are too many people on this boat.” Boarding had been briefly paused to adjust the list, the vessel’s leaning position.

As the ship swayed, passengers aboard had “oooohed” and “ahhhhed,” feeling like it had been a carnival ride. This is according to documented accounts and shared by Ted Wachholz, Executive Director of the

SS Eastland Disaster Historical Society.

At 7:20 am when the ship began to lean to port, Adam Weckler, the harbor master, had hollered up to Captain Harry Pedersen that the ship wouldn’t be allowed to leave until it had been even keeled.

Why Wasn’t Captain Pedersen Worried?

Captain Harry Pedersen had been familiar with the SS Eastland being “cranky” and unstable. This “top-heavy” passenger ship had been around over a decade, built in 1903. You see, cargo ships were more stable with their heavy loads carried at the bottom, while passenger ships had moving cargo on the top decks. So, the Eastland would naturally sway under shifting weight.

The SS Eastland had had troubles before. When overloaded with 3,000 people in 1904 the vessel nearly capsized. It happened again, listing dangerously, with 2,530 passengers two years later. These instances gave the Eastland the nickname of “the hoodoo boat.”

Another factor in the captain’s ease with this situation had been economical. After all, more profit could be made from paying passengers than with cargo.

Top Heavy Tipping

This “top heavy” feeling on the SS Eastland had been increased by the number of recently added life boats and vests for passengers. You see, new laws had been created since the Titanic’s tragedy just three years before.

The maritime law, “LaFollette Seaman’s Act,” had increased the required lifeboats from six to eleven. Plus, thirty-seven life rafts had been added at over a thousand pounds each. Six pound life vests were required for each of the previously allotted 2,570 passengers and crew.

Another factor had been the durable, cement flooring which had been spread across the highest deck.

Nobody had considered all the extra weight recently added or had thought to test the vessel’s abilities. Nobody had adjusted the amount of people who could ride aboard either. Without a keel, which is a weighted, balancing fin along the bottom of the hull, this steamboat swayed as people shifted on the decks above.

SS Eastland Capsized

At 7:28 the band suddenly stopped playing as the piano slid out from under the musician’s fingers. It slid to the port side along with a refrigerator which sadly crushed two women.

One of the five dock pilings, the ship had been tied to, ripped from the pier. It had happened so quickly that there hadn’t been time to deploy life saving gear: jackets, boats or rafts. A policeman standing on shore had said to a reporter, “It rolled like an egg in water.”

The Smithsonian Magazine article by Susan Stranahan

Passengers on the top deck had been flung into the water. Even those who knew how to swim had been struggling in layers of cloth.

Chicago Herald reporter, Harlan Babcock, had written, “When the boat toppled on its side those on the upper deck were hurled off like so many ants being brushed from a table. In an instant, the surface of the river was black with struggling, crying, frightened, drowning humanity. Wee infants floated about like corks.”

Parents clutched desperately to their flailing youngsters in the murky river. Some sank out of sight together, while others watched their children disappear below the sludgy water. “God, the screaming was terrible, it’s ringing in my ears yet.” a nearby warehouse worker shook his head as he talked with a reporter.

Joseph Erikson

Chief engineer, Joseph Erikson, had been concerned that the boiler may possibly explode, so he bravely climbed into the belly of the ship to open the boiler, relieving pressure. Erikson had remained aboard through the entire ordeal.

Rescue Efforts

Those at the docks hurled chicken crates and wooden boxes into the river hoping they could be used as floatation devices. These items proved helpful for thirty people. Unfortunately, some of these aids hit the struggling passengers sending them below the surface.

Elsie Newman had been on the deck waving to her friends at the dock when the ship shifted and she instantly found herself in the river. Weighted under heavy fabric she found it difficult to tread water, when suddenly someone began pulling at her buttoned boots from below. (Years later, she had shared this story with her grandson, Karl.) Her long hair had come loose from the combs as she had been dunked under several times by the person grabbing at her feet. When suddenly she felt someone pulling her hair. It had been a rescuer pulling her out of the dark saturation. After getting into the boat, she had realized that she no long had boots on her feet. Survivor’s guilt had begun to weave its way through her soul.

JV Brown, a port side survivor, admitted to punching those who clawed at him in the river. “No man is a hero underwater.” He had sadly stated in court weeks later.

Remember Uncle Sam? Well, Herman Krause believed his brightly colored suit had saved his life that day as rescuers spotted him easily. “Get Uncle Sam!” He had heard one of the men call out. They had managed to pull Krause into their boat and bring him to shore.

One woman had been seen placing her baby on a floating deck chair, giving it a kiss before sinking below the surface.

“People were struggling in the water, clustered so thickly that they covered the surface of the river.” Helen Repa, a Western Electric nurse recalled. “The screaming was the most horrible of all.” Helen had taken charge and directed a person to notify Marshall Field & Company requesting blankets. She had restaurants send hot soup and coffee to the hospital. Helen flagged down automobiles and loaded them with survivors. “I would simply go out into the street, stop the first automobile that came along, load it up with people and tell the owner or driver to take them.” she wrote later. “Not one driver said no.”

On shore a doctor would check each victim for a pulse. If there was evidence of life, a “Lungmotor” would be used. This two cylinder, hand pump device had tubes and a mask. Stricnine would be injected into the patient hoping to wake them, as well as protect them from the diseases carried in the polluted river. If there was no pulse the doctor would simply announce, “Gone.” Attendings with a stretcher would carry the body to a makeshift morgue at the Second Regiment Armory.

Trapped Inside The Eastland

Many passengers had been stuck inside the Eastland. Bobbie, the thirteen year old girl, had treaded water in between decks while her Uncle Olaf repeatedly dove deep into the ship. He had saved twenty-seven people, who all treaded water inside the vessel while waiting for rescue.

Out on the street a group of welders had shown up to cut into the hull and rescue those trapped inside. However, the police had set up a barricade and initially wouldn’t let the welders through.

When the welders were finally permitted to reach the ship, who should show up but Captain Pedersen, refusing to let them cut into his boat. Giving Captain Pedersen the benefit of the doubt, he had probably become overwhelmed and felt the need to control something. A welder firmly stated to the raging Captain, “Our job is to save lives, not worry about the ship.” The crowd grew enraged as the Captain continued to rant. The police arrested Captain Pedersen and had taken him away from the scene, most likely to calm the upset onlookers.

The Smithsonian Magazine article by Susan Stranahan

The welders were finally able to cut into the side of the ship freeing Bobbie, Uncle Olaf, the twenty-seven people and others trapped inside.

Rescuers came from all walks of life. Somewhere between 750 – 810 people had raced to the scene offering assistance. Anna Grimmer, a survivor, had said, “There were a million heroes that day. I don’t suppose anybody ever knew their names.”

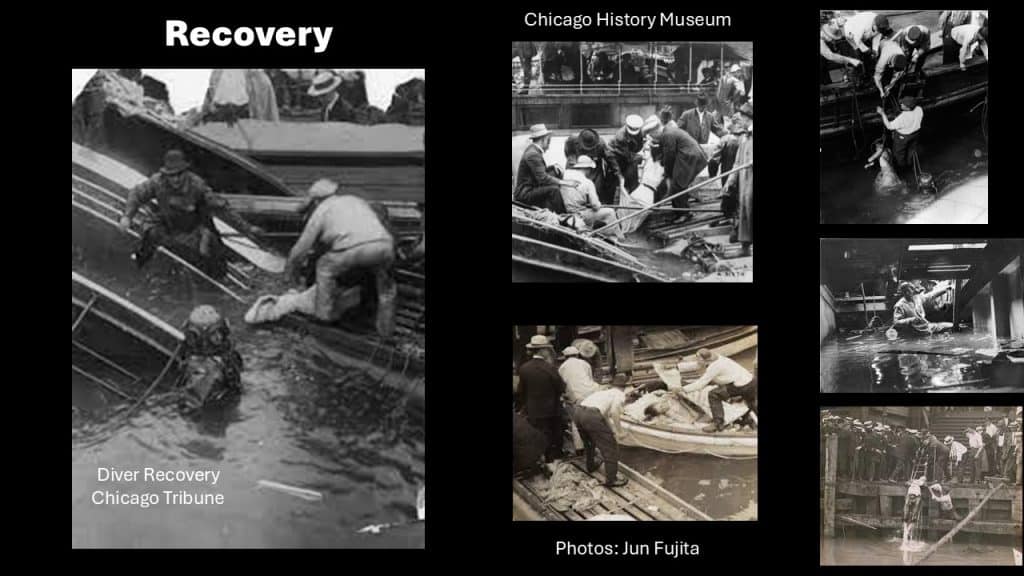

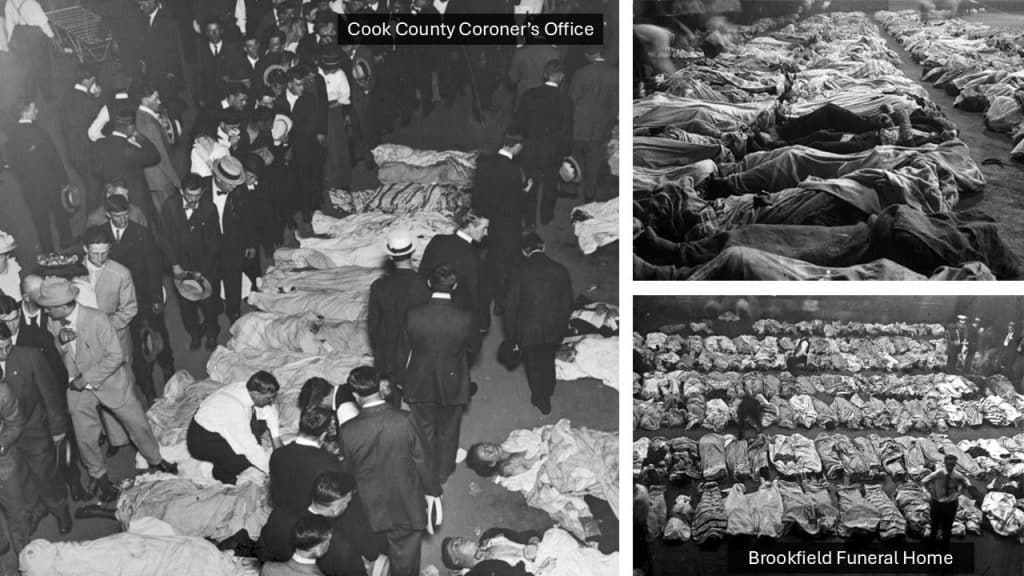

Recovery

Photo Credit: The Chicago Tribune

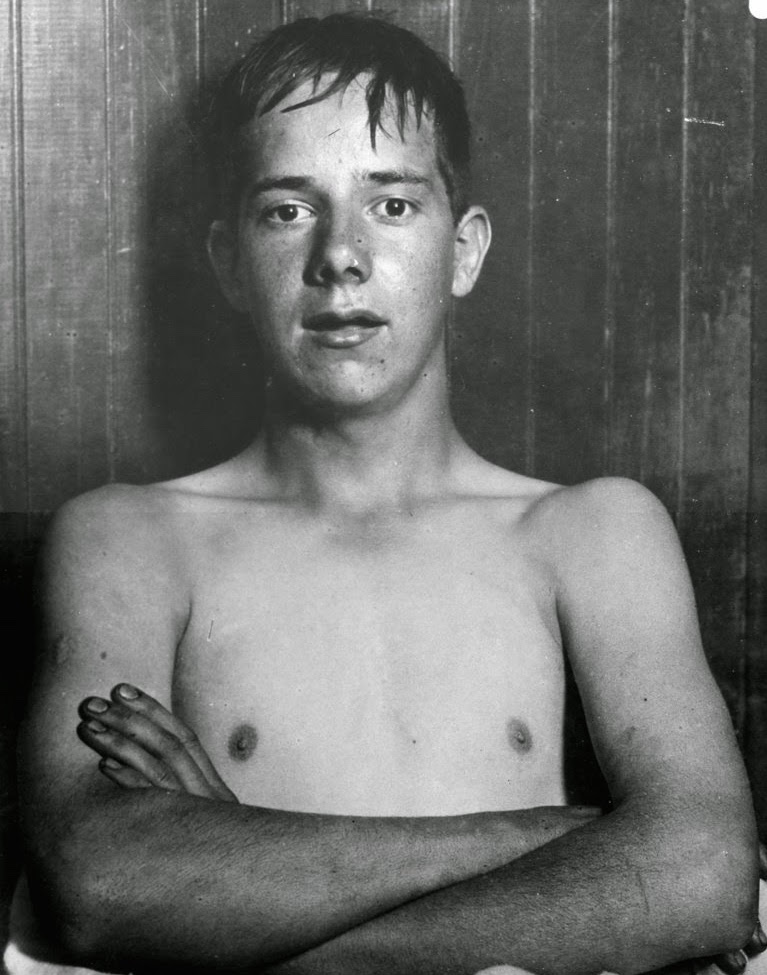

Upon hearing of the disaster, Reggie Bowles, eighteen, rode his motorcycle to the site. According to the newspaper, he had recovered thirty-seven dead bodies.

Later, he had died of Typhoid. It had been believed that he had contracted the disease from the filthy river water.

There had been a “bucket brigade” of bodies being handed down the line of volunteers to the armory, the makeshift morgue. Frank Swaggerd, a fireman, had been handed the body of a small girl. He clutched the child to his chest silently and collapsed. It had been his own daughter.

Photo Credit: The Chicago Tribune

Unclaimed bodies had been brought to the Second Regiment Armory, a makeshift morgue overseen by Coroner Peter Hoffman.

The Makeshift Morgue at the Second Regiment Armory

As the lines of grieving families, as well as the “morbidly curious,” had stretched around the block, Coroner Peter Hoffman stood at the entrance with a megaphone. “In the name of God: I ask you to go away and let those seeking relatives and friends come in and identify their dead.” Hoffman let in groups of twenty observers at a time.

Photo Credit: The Chicago Tribune

As families searched for their loved ones, some others who had entered the armory had stolen jewelry, watches and money from the dead bodies.

For several days volunteers led small groups up and down rows looking for birthmarks, scars, clothing, watches to help identify the deceased. When this happened, the volunteer would announce, “Identified!” A pair of stretcher-carrying volunteers would bring the body to a table where a proper death certificate could be registered. Sadly, some were misidentified causing compounded grief for all the families involved.

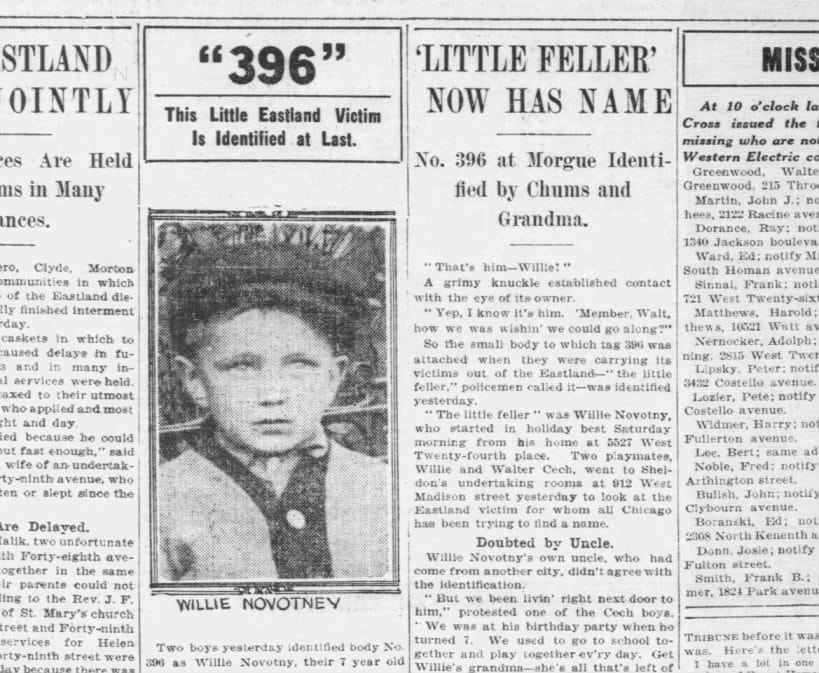

“Little Feller” Victim No. 396

As the grueling identifications continued through the week, one little boy had remained unidentified. The officers nicknamed him, “Little Feller.” His body was brought to his West Madison neighborhood where a young friend, Walt, recognized the small boy. “That’s him. – Willie.”

Little Feller’s Grandma confirmed this by Willie Novotny’s new suit pants worn special for the picnic. “If it’s Willie, he’s got pants like these,” she had said holding up a brown pair of pants. “It was a new suit he went to the picnic in, and two pairs of pants came with it. These are the others.”

Sadly, Willie’s parents, James and Agnes, along with his nine year old sister, Mimi, had all perished that day as well.

On July 31st more than 5,000 people attended the Novotnys’ funeral. The procession had extended more than a mile.

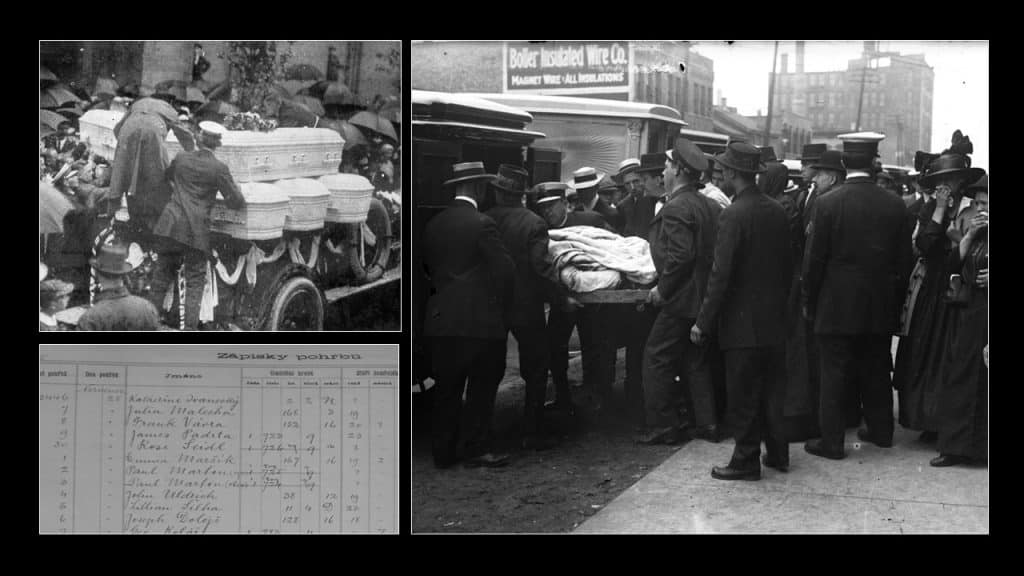

Funeral Funding and Preparations

Western Electric sprang into action providing $100,000 in relief funds and spear headed raising an additional $475,000. As well, the company had covered funeral and burial costs for their employees.

Otto Muchna, a Czech immigrant and funeral director, injected formaldehyde into bodies to preserve them using what was called a percolator, a glass bottle hung above with tubing into brachial artery. His wife, Mary, applied make-up to the bodies, helping them look more presentable for their families. Forty embalmers had worked continuously.

Fifty-two grave diggers had worked twelve hour shifts at cemeteries all around Chicago. At the Bohemian National Cemetery, where Czech families laid their loved ones to rest, a whole new section, Number 16, had to be added as nearly 150 new graves had needed to be dug.

So Many Funerals

Wednesday, July 28th witnessed seven hundred funerals and burials. The funeral homes didn’t have enough hearses, so Marshall Field & Company had provided thirty-nine trucks.

George, Josephine and their five children: Adella (15), Sylvia (13), George Jr. (9), Albert (7), and William (3).

Josephine’s sister, Regina, also lost her life that day.

An array of twenty-nine white caskets stood before the altar at St. Mary’s Church on that dark Wednesday.

Blanche Homolka had explained, “There was a shortage of coffins and so when my dear sister, Carrie, was brought home, they had placed her on a sort of wicker sofa.”

The Zastfra sisters, May, Antonie and Julie, had been excited to attend picnic with their friends, the three Pulifka sisters. Each young lady had hoped to meet a handsome gentleman in the near future and have her dear sisters and friends be the bridesmaids for the weddings. Instead, the Pulifka sisters had served as pallbearers for May, Antonie and Julie’s funeral.

One young Western Electric secretary had been cremated. Blazena Rebakova’s father had added an inscription with her remains at the mausoleum. “They were more interested in profits than the lives of the passengers. I am heartbroken at the loss of my loving daughter.”

Heartbreaking Statistics

After the Eastland had capsized, 844 passengers had died on the Chicago river, 20 feet from shore. Seventy percent of the victims had been under the age of 25. The majority had been women and children. 286 had been teenagers or younger. 40 children had been orphaned, as both parents had perished. Twenty-two entire families had been erased. This tragedy had far more deaths than the Chicago fire of 1871.

Investigations

Coroner Peter Hoffman, the man with the megaphone in front of the armory, had led the inquiry investigation about the SS Eastland catastrophe. The first suspects listed had been Captain Harry Pedersen, Chief Engineer Joseph Erickson and US Boat Inspector C.C. Eckliff. As the accused testified in front of the Grand Jury, a wider scope came into view. Attorney Hoin believed the true cause involved the greed of the ship builders, our government’s inspection system and the boat owners.

Through testimony it had been realized that no more than 1,200 people could have been safely transported on the SS Eastland, when on that day over 2,573 had been aboard.

Eventually eight men had been indited: Captain Pedersen, Chief Engineer Erickson and the Eastland‘s owners. The case dragged on and on for over 20 years. Only Chief Engineer Joseph Erickson, who had climbed into the belly of the ship to open the boilers, had been found in negligence. No fines or reprimand had been issued.

It wasn’t until 1950 that a formal report came out stating, “The cause of this disaster was improper procedural methods in the control of the vessel’s stability.” The victims and families had never received compensation.

The Eastland Refurbished

Get this. The SS Eastland had been dragged out of the river, refurbished and renamed, SS Wilmette.

She had been sold to the US Navy where she became a training ship. She was scrapped in 1947 following WWII.

Why Has The Eastland Tragedy Been So Unknown?

The Eastland tragedy had taken 844 souls, more than any other disaster on the Great Lakes. Why hasn’t it been remembered? First, World War I had been taking place at that time. The newspapers had been filled with stories of battles. Another factor, the people on board the Eastland had been working class immigrants, unlike the Astors and Guginheims, wealthy passengers on the Titanic. I believe the most pressing reason had been that many of the survivors and rescuers had never wanted to speak about the senseless loss of life on that tragic day.

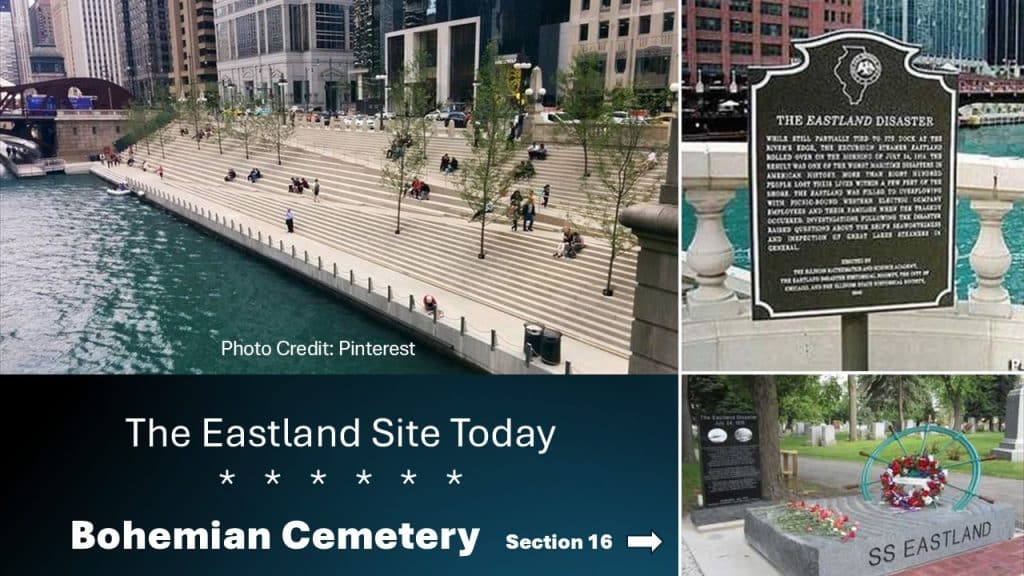

Eastland Disaster Historical Society

Bobbie, who had treaded water inside the ship, did share her story openly for decades. Her granddaughters, Barbara and Susan, are devout in remembering the passengers of the SS Eastland. Susan’s husband, Ted Wachholz, has taken the memory of these people to heart, too, as the founder and Executive Director of the Eastland Disaster Historical Society since 1998.

In 1989 a Historical Marker was dedicated to those victims of this tragic Great Lakes disaster. (top right photo)

Section 16 in the Bohemian Cemetery has a monument for the victims. (bottom right)

Last summer, July 24, 2024, a ceremony was held in remembrance of the victims, witnesses and rescuers. This year will be the 110th anniversary. They deserve to be remembered.

Related Links:

Here’s our Restless Viking video about this tragic day.

Eastland Disaster Historical Society website and Facebook page

Contact: PO Box 2013, Arlington Heights, IL 60006-2013 PHONE: 224-764-1284

Email: info@eastlanddisaster.org

Resources:

Kate Shusta – researcher for Restless Viking

“The Eastland Disaster” by Ted Wachholz Published 2005

The Smithsonian Magazine article by Susan Stranahan October 2014

“The Forgotten Disaster of the SS Eastland” video by Caitlin doughty

Karl Sup’s story of his grandparents’ survival of the Eastland.

“Flower In The River: The Eastland Disaster” article by Natalie Zett

Military History article

“Only The River Remains” blog post by Traci Rylands July 2015